The money the Arizona Game & Fish Department gets from the annual Big Game Super Raffle, which is now managed by the non-profit Conservation First USA, is required to be used for big game animal habitat improvements. But some of it is subsidizing ranchers that are permitted to graze cattle on public land managed by the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

The raffle is the result of the passage of HB 2064 by the Arizona Legislature in 1983. It authorized the Game & Fish Commission to gift up to two hunt permit tags annually to hunter groups for each of the state’s big game species on a trial basis. The organizations were allowed to auction or raffle off the tags and the proceeds were required to be used for “wildlife management.” The Legislature made the program permanent in 1986.

The Commission subsequently promulgated official rules for the donated tags in AAC R12-4-120. They require the hunter groups to transfer the annual proceeds generated from the donated tags to the Game & Fish Department for deposit in the program’s state account. The Department must then “coordinate” with the organizations to approve grants for projects that will benefit the big game species “for which the tag was issued.”

This sounds innocuous enough, but the use of the funds was subsequently politicized. It started in 1989 when the Legislature passed HB 2158, which established the Big Game Ranching Study Committee. This seven-member committee was tasked with studying the “feasibility of establishing a program for ranchers and landowners to recover costs associated with big game on their property.” It was created in response to complaints from ranchers that the state’s growing elk herds were reducing the forage available for their cattle on public land, and that the elk sometimes damaged their private land.

The Committee submitted its report in December 1989 and it included nine recommendations they had agreed upon. But it also included seven controversial recommendations proposed by the Committee’s ranchers that weren’t agreed to by all of the committee’s members. They included:

That the Game and Fish Department be held accountable, in the law, for any adverse effects on the livestock industry, whether on public or private land, caused by the state’s wildlife populations.

The Committee’s report didn’t result in any significant new legislation, but it did help motivate the Game & Fish Department to get friendlier with Arizona’s ranchers. Subsequently, in 1992 the Game & Fish Commission authorized the creation of an Arizona Elk Habitat Partnership Steering Committee to develop a program to “minimize conflicts between elk and other habitat users,” since elk compete with cattle for herbaceous forage. This resulted in the creation of regional partnership subcommittees to try and create diverse working groups to improve local elk habitat. Agency employees were designated as administrative support staff for the committees, and possible project funding partners were also invited to the meetings. Then, starting in 1994, the local subcommittees were tasked with proposing wildlife habitat improvement projects to a statewide partnership committee that could recommend approval of cost-share grants from the donated big game permit-tag money.

By 1996, nearly $325,000 in donated big game tag money had been approved for 31 projects to improve habitat for elk, deer, and pronghorn antelope. Also, the Commission dropped the word elk from the statewide committee’s name because the focus of the local subcommittees had expanded beyond elk habitat. It was changed to just the Arizona Habitat Partnership Committee (HPC). Most of the local subcommittees adopted the names of their regions.

The situation remains essentially the same today, except that in 2005 the Legislature increased the number of permit tags donated annually from two to three per each big game species. Also, the Game & Fish Commission convinced the participating hunter groups to cooperate in an annual fundraising effort. This resulted in the first Big Game Super Raffle in 2006, which raised $514,055. Since then, the yearly Super Raffle has generated increasing amounts of money. In 2019, for example, it brought in $669,065. The participating hunter groups, however, only provide one of the donated permit-tags they receive for each of the state’s 10 big game species to the Super Raffle. They auction or raffle off the other tags on their own. Those activities collected another $1,814,200 in 2019, so the total donation to the Special Big Game License Tag Fund in 2019 was $2,483,265. (Members of the hunting groups created a nonprofit 501(c)(3) corporation in 2007, the Arizona Big Game Super Raffle, Inc., to manage the annual event. They raffle off high-end hunting equipment at the Super Raffles to help fund their operations.)

The local subcommittees help forward HPC grant applications to the state HPC, which holds a meeting every year to review all of the grant proposals and forward them to the Arizona Game & Fish Department’s Director, who is required to “submit all timely and valid proposals to the Commission” for consideration and approval, as per AAC R12-4-120.C.

Since 1996 the attendance at most local HPC meetings has devolved to where most of the participants are now just government agency personnel, ranchers, and hunters, partly because the local and state HPC committee meetings are poorly publicized. Subsequently, the general public has little knowledge about what’s going on, despite the large amounts of public money involved.

Cartwright Allotment Water Project

I learned about the existence of HPC grants in the summer of 2019 and discovered there was a proposed grant from the Payson regional subcommittee of $100,000 to help fund a large livestock water project on the Cartwright Ranch. I knew the ranch held the grazing permit for the Cartwright grazing allotment, administered by the Tonto National Forest’s Cave Creek Ranger District. I also knew the allotment hadn’t been grazed for years because most of it had burned in the 2005 Cave Creek Complex Wildfire.

I checked the Tonto’s Schedule Of Proposed Actions (SOPA) and there was no mention of the Cartwright project, so I sent a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) information request to the Tonto on August 13 asking for copies of 2018 and 2019 annual operating instructions (AOI) for the allotment to see if grazing had been resumed. On August 29 the Tonto responded by providing the recent AOIs for the allotment, which included an AOI that showed grazing had resumed on the allotment in November 2017. This was done without any public notice, during a severe long-term drought, when many of the fences needed to be rebuilt, and most of the livestock waters were purportedly not operating.

The Cave Creek Ranger District subsequently issued a NEPA scoping letter on September 16 to solicit comments from the public about the proposed Cartwright Allotment Water Project. The letter said a 2008 memo of understanding between the Forest and the previous grazing permittee had put the allotment into a non-use grazing status to allow it to recover from the fire, but the resumption of grazing had recently been authorized for a new permittee.

The District’s scoping letter also mentioned that the allotment was permitted for up to 350 cows yearlong, as per its 2008 decision notice for the allotment. The 2017, 2018 and 2019 AOIs I obtained from my FOIA request showed the authorized cattle numbers significantly below that, so the proposed new livestock waters were obviously intended to help facilitate an increase in the number of cattle grazing the allotment up to the maximum allowable number. In fact, the project’s $100,000 HPC grant proposal stated in italicized text that its purpose was to “optimize production and utilization of forage allocated for livestock use.”

The project proposal called for the installation of several miles of plastic pipeline and some large water storage tanks to divert water from three perennial springs and one water well into numerous new livestock watering troughs on the uplands. Three of the pipelines would use the permittee’s water right to Seven Springs, which was fenced off from cattle. Two other pipelines would use the Forest’s water rights to two other springs. One these springs, Maggie May Spring, would be fenced to protect it from cattle, but the much bigger spring, Mashakattee Spring, would not. The proposal also called for another pipeline to use water from a Forest-owned well located beneath the perennial stretch of Cave Creek, downstream from Seven Springs. This part of the creek is also fenced to exclude cattle.

On September 23 I contacted the Forest’s hydrologist to learn more about the Tonto’s water rights identified in the project proposal. She explained that the Forest held a water right for Maggie May Spring for livestock watering. It also held a partial water right for Mashakattee Spring for domestic use, which was formerly used to supply two nearby recreational areas, and the defunct Ashdale Civilian Conservation Corps camp along Cave Creek.

The proposal to convert the Forest’s water right for Mashakattee Spring from domestic to livestock use prompted me to visit the spring with some friends on September 25. We discovered a large desert riparian area with a healthy population of native fish. An obvious concern was that the project’s proposal to divert up to 4,500 gallons a day from the spring would have negative effects upon this unique and important habitat. Furthermore, the proposal called for installing a storage tank near the spring to hold the water pumped from the spring, along with a new cattle watering trough near the tank, which could attract cattle to the riparian area and damage it.

In the written comments I submitted to the Cave Creek District Ranger about the project I questioned the claim that the project would improve riparian habitat conditions, specifically the plans to modify Maggie May and Mashakattee springs by diverting much of their water to cattle troughs. I suggested that the Forest should, instead, convert its water rights for the two springs to instream flow rights, in order to keep the water in them to protect the riparian habitat and wildlife they support. I also suggested that the Forest should restrict authorized cattle numbers on the allotment to low enough levels that the riparian grazing utilization guidelines included in the 2008 decision for the allotment could be met without diverting the springs.

Meanwhile, I had learned that the HPC grant proposal for the Cartwright Allotment Water Project would be forwarded to the state HPC’s annual review meeting to be held on January 11, 2020, in Phoenix. In early October I made my interest in attending the meeting known to the Department’s HPC Coordinator, and I received an email reply from him that information about the meeting would be posted to their HPC web page.

In early December I noticed the HPC web page had been updated to show that the location of the state HPC funding meeting in January would be the Game & Fish Department’s headquarters building in Phoenix. But it didn’t show the time the meeting would start, so I sent an email to the Department’s HPC coordinator on December 11 asking for the time. He replied that it would begin at 9AM.

I also sent the Game & Fish Commission’s Chairman Eric Sparks an objection letter on December 11 describing my opposition to the Cartwright project’s approval. It mirrored the points I’d raised in my written comments to the Tonto, and it also informed him that I planned to attend the January 11 meeting to voice my concerns in person.

Forest Service Approves Cartwright Project

On December 31, 2019, Cave Creek District Ranger Micah Grondin issued a decision memo to approve the implementation of the Cartwright Allotment Water Project. The use of a memo, instead of a decision notice, categorically excluded the decision from NEPA analysis, and prevented it from being appealed. He conceded that the permittee wanted to begin grazing the full permitted number of 350 cattle in 2020. This was confirmed when the District issued the 2020 AOI for the allotment, which authorized up to 350 cattle.

Grondin also glossed over the damage that would be inflicted upon the springs by diverting water to the new cattle troughs. In response to my suggestion that the Forest should convert its water rights to Maggie May and Mashakattee springs to instream flow rights, he wrote that the, “State of Arizona does not currently have an established process for converting a certified water right like that which is held by the Forest Service.” This prompted me to do some amateur legal research. I found state law ARS § 45-172.A which did, indeed, state that existing water rights can only be converted to instream flow rights that are owned by “the state or its political subdivisions.”

But I also discovered that all National Forests hold federal reserved water rights which were established when the forests were created. These federal water rights aren’t subject to state beneficial use requirements and cannot be lost due to nonuse. In other words, the Tonto, and all of Arizona’s national forests, can make de facto conversions of their federal water rights to instream flow rights by simply leaving the water in the springs and streams.

The Cartwright project’s decision memo also included two theories often used to justify projects to build new livestock waters in the Southwest – both of which deserve scrutiny. First, Ranger Grondin claimed that the new livestock waters would help protect the riparian areas on the allotment by luring cattle away from them. But his decision notice included the approval of the new livestock watering trough that might be located near the new water storage tank near Mashakattee spring. Moreover, research (Carter 2017) has shown that building upland livestock waters provides insufficient protection to riparian bottomlands if cattle aren’t fenced out of them, and primarily facilitates increased grazing in the uplands. And how does diverting significant portions of water out of desert springs protect them?

The other popular theory he repeated was that the new livestock waters would improve upland habitat by providing more water sources for the local wildlife, which in the case of the Cartwright project, was supposed to be desert mule deer. But there is a lack of research showing that desert mule deer benefit from livestock waters during the cool seasons or wet years, as they are adapted to arid lands. However, they have been found to concentrate around water sources in dry months or years. Subsequently, the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA) habitat guidelines for mule deer suggest that water sources should be no more than 3 miles apart, so that deer can be within 1.5 miles of surface water. These distance-to-water guidelines aren’t based upon hard science, but an assumption that, “Well distributed water sources likely distribute deer better through their habitat, thereby allowing them to occupy previously unused areas.”

But a review of the map showing the locations of the Cartwright project’s proposed livestock waters showed that only a few of them would be more than about 1.5 miles from the numerous springs in the area, or the perennial stretch of Cave Creek. Obviously, the benefits from the new livestock watering troughs would be negligible for the local desert mule deer.

Furthermore, research has shown that creating more dependable upland water sources, for both deer and cattle, doesn’t always improve mule deer habitat. Cattle and mule deer typically have a minor dietary overlap, because cattle prefer to graze herbaceous plants and the deer prefer to browse woody plants. This is often used, as it was with this project, as a justification for permitting increased cattle grazing in mule deer habitat. But much of the vegetation on the Cartwright allotment is Sonoran Desert scrub, semi-arid grassland, and chaparral, so there’s not a lot of herbaceous vegetation. It’s the same situation on all of the Tonto’s desert grazing allotments. This forces cattle to eat a lot of brush to survive. In fact, research has shown that perennial grasses never comprise more than 50% of the forage consumed by cattle in the desert Southwest (Rosiere 1975), and that cattle are forced to rely on eating desert shrubs during the hot and dry summer months (Smith 1993). Subsequently, cattle compete with desert mule deer for browse forage on arid allotments during the toughest times – the hot summers and droughts (Knipe 1977, Scott 1997, Severson 1983, Short 1977, Swank 1958), especially in the xeroriparian corridors (dry washes) preferred by the deer. The consumption of vegetation by cattle during dry times also negatively affects the deer habitat component of cover, especially for newborn fawns (Horejsi 1982). The bottom line is that new livestock waters facilitate desert mule deer habitat degradation by helping to keep cattle on the land during hot and dry times.

Additionally, Grondin’s rubber stamp approval of the Cartwright HPC project proposal facilitated an increase in livestock grazing on the allotment from the 1,182 AUMs authorized in 2019, to the 4,275 AUMs authorized in the 2020 AOI, or about 376%. This would obviously have a negative impact on local wildlife habitat.

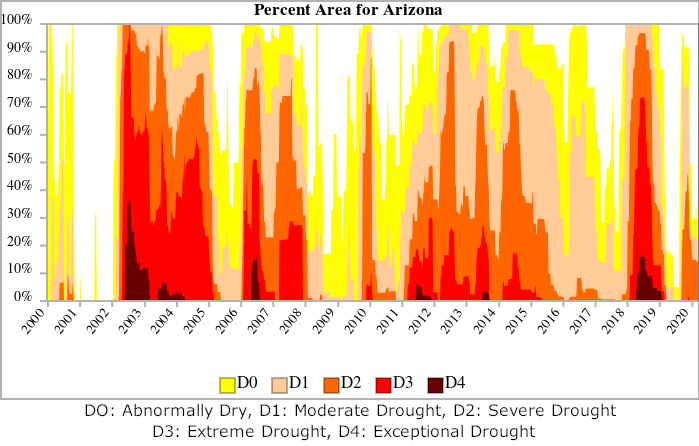

The 2020 AOI also appears to violate the Drought Guidelines included in the Forest Service’s Southwestern Region’s Grazing Permit Administration Handbook (FHS 2209.13, Chapter 10). The guidelines recommend that pastures should be rested from cattle grazing “for at least on entire growing season or more following severe droughts.” They also state that decisions to stock allotments after droughts should consider the value of “wildlife habitat.” But despite the severity of the ongoing drought in 2019, the 2020 AOI for the Cartwright allotment authorized the entire permitted number of 350 cows.

Moreover, Grondin’s use of a NEPA categorical exclusion to authorize the Cartwright project is more questionable than most. It approved an extensive new livestock watering system that wasn’t included in 2008 environmental assessment(EA) of the allotment. Furthermore, Mashakattee Spring wasn’t even mentioned in the EA, nor was it mentioned in the biological assessment the Forest sent the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) in October 2007 to obtain a concurrence that their livestock management plan for the allotment complied with the Endangered Species Act. This seems to ignore the forest-wide management prescription included in the Tonto National Forest Plan which states:

Locate and survey all potential Gila Topminnow sites. Where feasible stock sites, monitor for success, and restock if necessary.

Mashakattee Spring is an obvious potential site for the endangered Gila topminnow (Poeciliopsis occidentalis).

State Habitat Partnership Committee Meeting, January 11, 2020

I left my house very early on the Saturday morning of January 11 because it was a long drive across town to the Game & Fish Department’s building and I wanted to make sure I got to the state HPC’s annual review meeting before its 9 a.m. start time. I was surprised when I got there a little before 8 a.m. I saw there were a lot of vehicles in the parking lot and people were going inside, so I decided to go in too, instead of waiting outside.

In the lobby I encountered the Department’s Habitat Enhancement Coordinator. He said the meeting was about to start and guided me back through the building’s hallways to the meeting room. I was puzzled by the change in the meeting’s start time, so on the way back I asked him, “This is a public meeting, isn’t it?”

“It’s not a public meeting, according to the Arizona Secretary of State’s rules, but it’s a meeting that’s open to the public,” he replied. I didn’t believe that was true, but I didn’t say anything.

The meeting was being held in a large room and there were at least 40 people in attendance, comprised almost entirely of hunting group representatives and Department personnel. They were settled in their seats at long tables, with their documentation spread in front of them, so they had obviously received prior notice of the correct meeting start time. I picked up a copy of the meeting’s public notice and agenda from the handouts table and saw that it showed an 8 a.m. start time. (After I returned home later that day, I checked the state HPC home page again to see if I’d missed something. There still wasn’t any HPC meeting start time or agenda on it. I also checked the Arizona Public Meetings website, but there was no notice and agenda about the HPC meeting posted there either.)

I sat down in the back of the meeting room while the meeting’s chairperson, Arizona Game & Fish Commissioner Leland “Bill” Brake, who is also a public land rancher, made some opening remarks. He said that HPC grants to ranchers are “necessary” for good ranch management, and are an “appropriate” use of HPC funds because, “project’s that are good for wildlife are good for livestock too.” He told the hunters at the meeting, “Thank you for what you do for the ranching community.” He also suggested that HPC grants are better for ranchers than federal EQIP money because ranchers don’t have to do anything that they don’t want to in order to get HPC grants, while EQIP funds often have “too many strings attached.” This helped explain to me why HPC projects were being rubber stamped by Forest Service and BLM land managers.

Then the Department’s HPC Coordinator reviewed the meeting’s agenda and explained that a call to the public had been added to the beginning, wherein any member of the general public in attendance would have the opportunity to make comments up to three minutes long. I realized that if I hadn’t arrived at the meeting until 9 a.m., the starting time I’d been given, I would have missed my opportunity to submit comments about the Cartwright water project.

I raised my hand and was recognized to speak. I had a lot to say, but since I only had three minutes, I had to restrict my comments to the damage I believed the proposed water diversion at Mashakattee Spring would inflict upon its riparian habitat and native fish population. The attendees listened politely, although many seemed surprised and confused by my presence. Commissioner Brake responded to my comments by explaining that, “the project has already been scored.” He thanked me for bringing the issue to their attention, and said that just because a fence to protect the spring wasn’t include in project, “that doesn’t mean it won’t happen.” But he added that he didn’t mean that it would happen either.

The meeting then proceeded with the Department’s HPC Coordinator working down a list of the year’s proposed HPC project’s that were projected onto a screen on the wall behind him. He gave a brief description of each project, and often solicited comments about them from the hunting group representatives and agency personnel before they were recommended for approval. He also noted the dollar amount of each HPC grant and identified the big game species it was supposed to benefit. There was a finite amount of HPC money available for each big game species, so he was sometimes forced to get creative and use combinations from the various pots of species money in order to fully fund a project. Most of the HPC grants definitely benefited wildlife, but there were also some that benefited ranchers. In addition to new livestock waters, there were vegetation manipulation projects to mechanically and chemically kill juniper and mesquite trees to promote the growth of grass, which is preferred by cattle. These were justified as being big game habitat enhancement projects because elk like to eat grass too, and pronghorn antelope prefer open grasslands. One of those projects involved the aerial spraying of a dangerous herbicide. But there weren’t any projects to conduct research to determine if the strategies employed in HPC projects had produced the presumed results.

The ambiguous purpose of some of the projects was highlighted when the Department’s Habitat Enhancement Coordinator described one of the proposals as being “truly a wildlife project.” The grant application review process was supposed to end when all of the HPC money raised for the year was spent, but I left after they approved the $100,000 HPC grant to help fund the Cartwright water project.

During a break in the proceedings, however, I had spoken to the Department’s Habitat Enhancement Coordinator and he admitted that I was the first member of the general public that he knew of who had attended one of their annual state HPC funding meetings. I didn’t doubt that was the case.

Afterwards I learned that $2,227,560 in HPC grants had been forwarded during the meeting to the Department’s director for approval using the funds raised in 2019 from donated big game hunt permit-tags.

HPC Grants Have Helped Increase Grazing On Other Allotments Too

The Cartwright isn’t the only public land grazing allotment in Arizona where HPC grants helped to facilitate increased livestock grazing, or maintain existing livestock numbers, during the Southwest’s ongoing megadrought. There are numerous examples on public land ranches throughout the state, including several other ranches on the arid and rugged Tonto National Forest that have received four or more HPC grants in the last several years.

Commissioner Bill Brake

Brake’s membership on the Arizona Game & Fish Commission, especially his involvement with HPC grants, obviously raises some conflict of interest questions because he is a co-permittee on at least one BLM and four Forest Service grazing allotments. The BLM allotment is the Rose Tree allotment (#6043), part of the Rose Tree Ranch, which also holds Arizona state grazing lease #05-000138, through the Rose Tree Cattle Co., LLLP.

As for the Forest Service allotments, he is a co-permittee through the J Bar B Cattle Co., LLP, for the Campaign and Poison Springs allotments on the Tonto National Forest, and the Wildcat allotment on the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest. The three allotments are managed together as the Rafter Cross Ranch.

He’s also a co-permittee through the Rockin Four Ranch, LLC, for the Hicks-Pikes Peak allotment on the Tonto, because the J Bar B Cattle Co., LLP, is one of the Rockin Four’s owners. The ranch’s other current partners hold grazing permits for other public land grazing allotments.

Before Brake was appointed to the Commission on January 24, 2018, he benefited from at least three HPC grants for the Rose Tree Ranch. HPC grants #09-501, #13-511, and #17-501 were all for livestock water developments, and totaled $34,209, although these project proposals said there had been several previous HPC grants for the ranch.

The state HPC has held two funding meetings since Brake was appointed – one in January 2019 to recommend the approval of HPC grants from the money raised in 2018, and the January 2020 meeting that recommended grants from money raised in 2019. The lists of HPC projects approved those years do not appear to include any grants for projects located on any of the public land grazing allotments for which he is a co-permittee. But it’s difficult to tell because of the limited and cryptic information the Department provides about approved HPC projects.

Commissioner Brake is also familiar with the other government assistance programs that benefit Arizona ranchers, as shown in the tables below for the ranches he co-owns. That includes at least a couple of awards from the Arizona Game & Fish Department’s Heritage Fund. In 2003 he received compensation of an undisclosed amount from the fund’s public access monies for the Rose Tree Ranch to allow people to travel across the ranch’s private land to access adjacent public land. And in 2006 the fund disbursed $10,000 from its habitat improvement monies to help build a fence on the Rafter Cross Ranch to protect Campaign Creek from cattle.

| YEARS | PROGRAM | AMOUNT | PROJECT NAME |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007-2009 | EQIP | $56,450 | |

| 2007 | LCCGP #07-76 | $83,575 | Grassland Restoration, Livestock Water |

| 2009 | HPC #08-525* | $21,600 | Brush Removal |

| 2010 | HPC #09-501 | $22,556 | Chappo Betty Livestock Water Development |

| 2012 | HPC #11-503* | $20,000 | Kill Coyotes for Pronghorn & Mule Deer Fawn Protection |

| 2012-2021 | LFP | $58,242 | |

| 2014 | HPC #13-511 | $4,846 | Abner Water Well Redevelopment |

| 2014 | HPC #13-519* | $10,000 | Kill Coyotes for Pronghorn & Mule Deer Fawn Protection |

| 2015 | HPC #14-520* | $10,000 | Kill Coyotes for Pronghorn & Mule Deer Fawn Protection |

| 2016 | LCCGP #16-14 | $39,094 | Livestock Water |

| 2018 | HPC #17-501 | $6,807 | Replace Schock Windmill With Solar Water Pump |

| 2019 | HPC #18-523* | $10,000 | Kill Coyotes for Pronghorn Fawn Protection |

| 2020 | HPC #19-509* | $10,000 | Kill Coyotes for Pronghorn Fawn Protection |

| 2021 | HPC #20-511* | $15,000 | Kill Coyotes for Pronghorn Fawn Protection |

| 2022 | APWIAP** | $32,000 | Rebuild Livestock Fences & Waters Burned in the 2022 Elgin Bridge Fire |

| 2022 | LFP | $20,237 | |

| 2022-2023 | ELRP | $20,147 | |

| 2023 | HPC #22-508 | $3,300 | Mustang Mountains Water Development |

| $443,854 | TOTAL 2007 - 2023 | ||

**Temporary program administered by the Arizona Dept. of Forestry & Fire Management.

| YEARS | PROGRAM | AMOUNT | PROJECT NAME |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | BOR | $73,980 | 1992 AMP for Campaign allotment |

| 1999 | EWP | $37,888 | Paid to Take Cattle Off the Land During Drought |

| 2006 | Heritage Fund | $10,000 | Campaign Creek Riparian Fence |

| 2006 - 2016 | EQIP | $207,576 | Campaign allotment $133,096 Wildcat allotment $74,480 |

| 2015-2016 | LFP | $198,402 | Campaign allotment $142,264 Wildcat allotment $$56,138 |

| $527,846 | TOTAL 1992-2020 | ||

An allotment management plan (AMP) for the Poison Springs allotment was completed in 1987, long before the current boundaries of the Poison Springs allotment were set in 2017. The Campaign allotment's current AMP is the proposed action described in its 2011 (EA). The 1992 AMP was funded by a grant from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation as part of a mitigation plan for the local wildlife habitat that was flooded when the height of Theodore Roosevelt Dam was increased.

| YEARS | PROGRAM | AMOUNT | PROJECT NAME |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 - 2019 | EQIP | $231,089 | |

| 2015 | LFP | $122,105 | |

| $353,194 | TOTAL 2008-2020 | ||

NOTE: In 2020 $65,784 in federal Burned Area Rehabilitation (BAR) funds were approved to help rebuild livestock fences & waters damaged in the 2020 Salt Fire. The money was shared among six grazing allotments, including this one, in the Tonto National Forest's Globe Ranger District.

The current allotment management plan was completed in 1992.

Financial information acquired through Freedom of Information Act requests and Public Records Requests.

SB 1200

The appointment to the Game & Fish Commission of someone with the potential conflicts of interest as Commissioner Brake probably wouldn’t have happened before 2010, when the Legislature passed SB 1200, which drastically changed the way the commissioners are appointed. It was a strike-all bill promoted by the National Rifle Association (NRA) that created a five-member Arizona Game & Fish Commission Appointment Recommendation Board to identify the only candidates the Governor can choose from in order to appoint new members to the Commission. At least one of the five Recommendation Board members is designated by the director of an Arizona cattle rancher group. Three of the Recommendation Board members must be designated by the directors of three Arizona hunter groups. The definition of one of the hunter groups is so specific that it virtually guarantees a Board member from the Arizona Sportsmen for Wildlife Conservation, which receives the donations generated from sales of the state’s Conserving Wildlife specialty license plates. Only three members of Board must be present to constitute a quorum.

Before the passage of SB 1200, the Governor could appoint almost anybody to the Commission, subject to State Senate approval, as long as they had knowledge about wildlife conservation.

Other Questionable HPC Grants

Many HPC grants for projects on public land ranches have helped to fund a variety of different types of water projects that were justified with claims they would help both cattle and wildlife. But, as shown by the Cartwright project, some of them provided little, if any, net benefit to the local wildlife.

Also, there have been HPC grants for projects which benefited ranches that used holistic resource management (HRM) grazing systems, which have been discredited by scientific research, and can be particularly damaging when implemented on arid lands.

Another big category of questionable HPC grants are those that kill “invasive” woody vegetation – usually mesquite or juniper trees. These vegetative manipulations, typically labeled as grassland or watershed restoration projects, are intended to promote the growth of grass, which benefits cattle and a few species of big game – such as elk and pronghorn antelope. They sometimes involve the aerial spraying of dangerous herbicides, which can leave the land practically denuded for several years – especially during drought.

These vegetation conversions, as you might imagine, are very expensive and many will need to be repeated every few years because climate change is causing vegetative communities to migrate in the West. Another cause of the recent proliferation of woody plants is that cattle prefer to eat the herbaceous vegetation which provides the fuel for the milder, periodic fires that naturally control woody vegetation.

The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) has disbursed many grants for these types of projects, purportedly to reduce nonpoint source pollution downstream. In 2015 ADEQ awarded the Arizona Game and Fish Department with Water Quality Improvement Grant (WQIG) #EV15-0005 for $412,000. Game and Fish provided $274,666 in matching funds to get the grant, and that included $35,000 of HPC money. (The matching funds they provided also included $135,000 from the Department’s Heritage Fund.) The Department likely used most of this ADEQ grant money for tree removal projects.

Then in 2020 the Department received WQIG #EV-19-0010 from ADEQ for $109,176 to remove mesquite trees from the Altar Valley, in the Sonoran Desert southwest of Tucson. The project record didn’t specify the sources of the matching funds the Department provided to get the grant, although it mentioned they could include “AZGFD state funding.” The Department had previously approved two HPC grants, #17-525 for $15,000, and #18-521 for $50,000, to kill mesquite trees in this area on the Santa Margarita Ranch. These grants were justified as creating more pronghorn antelope habitat, as this game species prefers open spaces.

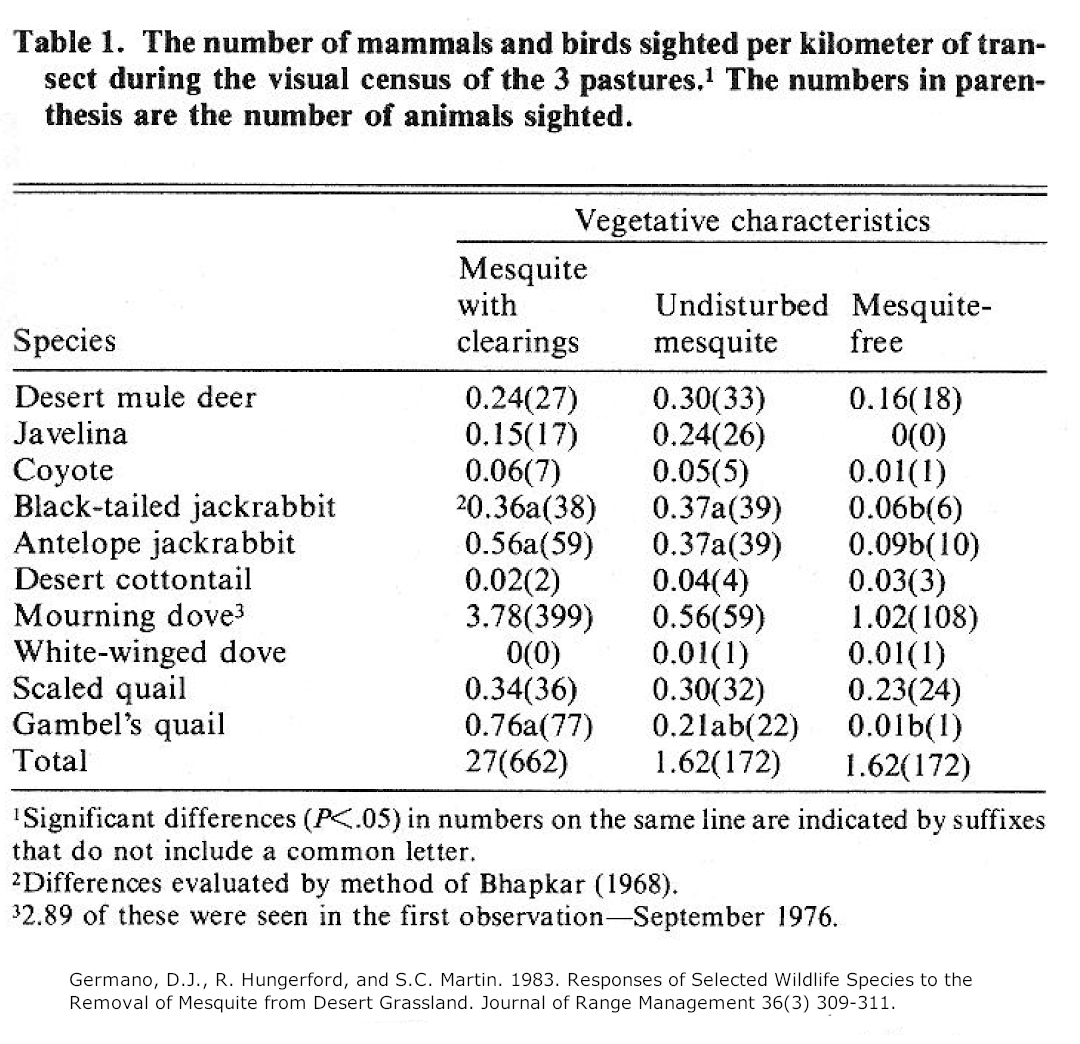

Mesquite trees are often labeled as “invasive” and targeted for removal in rancher-friendly projects. But that’s a pejorative adjective that denigrates their role as a keystone plant in the desert Southwest. Mesquite bosques (forests) are an important and endangered riparian habitat in Southwestern desert bottomlands. And research has shown that desert plant species (Tiedemann 2004), and wildlife species (Germano 1983), including mule deer, are more numerous in areas with mesquite trees.

At higher elevations, juniper trees are the target of these vegetation manipulation projects, and elk are usually the local big game species they are intended to benefit.

At higher elevations, juniper trees are the target of these vegetation manipulation projects, and elk are usually the local big game species they are intended to benefit.

Landowner Relations & Habitat Enhancement Program

HPC grants are part of the Department’s multi-million dollar Landowner Relations & Habitat Enhancement Program, which includes other types of assistance for ranchers. The money comes from a variety of sources, including the Department’s Heritage Fund. The other assistance is administered with much less transparency than HPC grants.

The hunter groups that raised funds for HPC grants in 2019 included the Arizona Antelope Foundation, Arizona Bowhunters Association, Arizona Deer Association, Arizona Desert Bighorn Sheep Society, Arizona Elk Society, Mule Deer Foundation, Arizona Mule Deer Organization, National Wild Turkey Foundation, and Safari Club International – AZ Chapter. These were the same ones that provided input on the review of HPC grant applications at the state HPC’s funding meeting in January 2020.

These nonprofit organizations regularly provide dedicated volunteers that contribute many hours of work to complete HPC projects on the ground. But some project work is completed by private contractors. With more than $2 million in HPC grants being disbursed each year, it’s reasonable to suspect that there are contractors who have made a lot of money from the program by building fences, installing livestock waters, and killing trees. And nothing prevents these contractors, or the ranchers that receive HPC grants, from being influential financial donors to the hunter groups that participate in the HPC program, or being members of the local HPC committees that recommend grants for approval by the state HPC.

Lack of Transparency

The Department’s administration of HPC grants needs to transparent because every grant should be objectively assessed for its net benefit to the local wildlife habitat. If a proposed project would facilitate more cattle on the land, or if it would build waters that helped cattle stay on the land longer during dry times, it must be evaluated to see if the anticipated habitat improvement would outweigh the escalated competition for forage and overall habitat degradation that the increased livestock grazing that would create. Sufficient vegetation to provide quality cover and forage is often more important than surface water for arid land wildlife species – and livestock grazing negatively affects both of those habitat components.

More public participation could help prevent the approval of HPC grants that are more like ranching subsidies than wildlife habitat improvement projects. Arizona has an open meeting law (OML) that requires state government agencies to publicly post meeting agendas, as per ARS § 38-431.02, and meeting minutes, as per in ARS § 38-431.01.

And according to ARS § 38-431.1 these requirements apply to the following state government entities:

Advisory committee” or “subcommittee” means any entity, however designated, that is officially established, on motion and order of a public body or by the presiding officer of the public body, and whose members have been appointed for the specific purpose of making a recommendation concerning a decision to be made or considered or a course of conduct to be taken or considered by the public body.

This would, obviously, include the state Habitat Partnership Committee because it is officially tasked with recommending the approval of HPC grants to the Department’s director. The failures of the HPC committees to fully comply with the open meeting law prompted me to submit a written complaint to Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich’s Open Meeting Law Enforcement Team (OMLET) on January 16, 2020. Arizona Game & Fish Department Director Tye Gray responded with a letter on February 18 wherein he admitted that the state committee was subject to OML requirements. He disagreed, however, that the local HPC committees were legally required to comply, because the local HPC subcommittees aren’t subject to the open meeting law, as they “were were never established by law or an official action of a public body.”.

Hopefully, the Department will do a better job of complying with the OML. But the Arizona Game & Fish Commission and Department doesn’t have a good history of compliance, as documented in a 2013 Performance Audit by the Arizona Office of the Auditor General. And the state HPC, as I described above, did not post a meeting notice with a start time or agenda to the Department’s HPC web page before its January 11, 2020, meeting. Nor have any minutes from that meeting been posted to the page. There was a link to the HPC’s previous minutes from their July 26, 2019, meeting. But they lacked the legally required information about the date and place of the meeting. That might be because it was hosted by the Arizona Cattle Growers’ Association during its summer convention at the We-Ko-Pa Resort and Convention Center. In fact, the HPC was on the convention’s agenda as part of a breakout session.

During Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey’s January 2020 State of the State address he said:

There are hundreds of unelected boards and commissions that exist in a dark corner of state government – often escaping accountability and scrutiny. We’ve sought to chip away at the deep-rooted cronyism. But there’s still too many insiders and industry good ol’ boys. It’s time to clean this up.

This accountability and scrutiny, however, doesn’t appear to apply if the good ol’ boys are helping cattle ranchers.

Updates

On August 6, 2020, the Arizona Game & Fish Department released its 2020 HPC grant proposal evaluation criteria which were touted as being more “objective.”

On January 9, 2021, the annual state HPC funding meeting was conducted using an online video conference because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The state HPC recommended 2020 HPC grants for approval by the Director. They included recurring amounts for HPC projects that were authorized in previous years. During the meeting I was allowed to ask questions, like all of the participants, and wasn’t limited to a 3-minute public comment period.

On On October 26, 2021, I revisited Mashakattee Spring on the Cartwright grazing allotment with some friends to see the changes that had been made by the completion of the Cartwright water project. I was pleased to find that there wasn’t a new livestock watering trough in the spring’s riparian habitat near the water storage tank by the well, like the project project proposal and decision notice said there would be. I was also happy to see that some new fence had been constructed above the spring, on the north side of the canyon, to protect it from cattle – even though it had a barbed lower wire, instead of a wildlife-friendly smooth lower wire. In a subsequent conversation with a Cave Creek Ranger District range management specialist, I was told the plan to put a watering trough in or near the riparian area had been abandoned. He also explained that the fence I saw was a repair of the south boundary fence of the Cartwright grazing allotment’s Humboldt pasture, so Mashakattee Spring is located in a holding pasture that won’t be included in the ranch’s regular grazing rotation. He also promised that the use of the barbed lower wire on the new fence would be investigated.

On February 2, 2022, the Mohave County Attorney’s issued a legal finding that they concurred with the Game & Fish Department’s position that their local Habitat Partnership Committees are not subject to the state’s Open Meeting Law because they aren’t officially public bodies.

On March 12, 2022, the 2021 HPC grants were recommended for approval.

On Friday December 30, 2022, Gov. Doug Ducey nominated Jeffrey Buchanan for the Arizona Game and Fish Commission to replace Leland “Bill” Brake, whose term in expiring. It was one of Ducey’s last acts before leaving office.

On January 9, 2023, the 2022 HPC grants were recommended for approval.

In August 2023, the Arizona Game & Fish Department released a Habitat Partnership Committee Charter.

On November 20, 2023, the 2023 HPC grants were recommended for approval.

On November 18, 2024, the 2024 HPC grants were recommended for approval, including another grant for the Cartwright Ranch. It was HCP grant #24-604 for $50,000 for new livestock waters in the Bronco pasture of the Cartwright allotment.

In January 2025, Arizona Rep. Gail Griffin (R-Hereford), chair of the House Natural Resources, Energy and Water Committee, introduced HB 2083, which would require that at least one member of the five-member Arizona Game & Fish Commission be rancher. Less than 0.5% of Arizona’s population are ranchers, and many of them don't rely on ranching for their primary source of income.

2 thoughts on “Arizona Game & Fish Department Helping Wildlife That Go Moo”

The livestock loss board meetings are another example. I’ve attended to try to understand the process, but the information given is sparse – they vote on reimbursements by grant numbers, not names or locations. It’s impossible to know what’s really going on. They also do not record them.

I have investigated the Arizona Livestock Loss Board and you can read my findings in this May 2022 blog post on this site: https://azgrazingclearinghouse.org/az-livestock-loss-board/