The Arizona Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Gila District Office proposed to increase cattle grazing in the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area (SPRNCA) by about 375% in a draft resource management plan released June 29, 2018.

The SPRNCA is a special place and was the BLM’s first nature preserve, a product of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976 passed by Congress with the support of President Jimmy Carter. The passage of FLPMA was a historic environmental achievement because it changed the BLM from an agency focused on commodity production into one that is required to administer the public lands under their jurisdiction according to the multiple use doctrine, like the U.S Forest Service.

Another important environmental law, the Endangered Species Act (ESA), had been signed by President Richard Nixon in 1973, less than four years before Carter took office. One of Carter’s environmental priorities was to protect endangered species habitat by bringing it into public ownership, and the passage of FLPMA meant that BLM lands could be managed for wildlife too. Congress significantly increased the funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund and boosted the budget of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in order to help the Carter administration acquire more public land for wildlife habitat protection.

The USFWS, under the leadership of Secretary of the Interior Cecil Andrus, subsequently began conducting surveys across the U.S. to identify important wildlife habitat that could be purchased and brought under federal ownership. In January 1978, after a suggestion from the Nature Conservancy, they surveyed the privately owned San Pedro River from Hereford to Winkleman. Their report said the river had “the richest assemblage of land-mammal species” in the U.S., and they designated the San Pedro as a priority for federal acquisition because of its unique and endangered desert riparian ecosystem. The lands identified for purchase were comprised of the San Juan de las Boquillas y Nogales and San Rafael del Valle Spanish land grants. They were owned by Tenneco, which had bought them in 1971 as a real estate investment. The USFWS, however, wasn’t able to buy the land from Tenneco because President Ronald Reagan put an end to Carter’s ambitious public lands acquisition program when he assumed office in 1980.

In the meantime, Arizona Governor Bruce Babbitt was worried about the future of the sensitive wildlife habitat owned by the Arizona State Land Department. Under the State Enabling Act passed by Congress in 1910, these lands had to be used to generate revenue for the beneficiaries of the State Trust, the largest being K-12 public education. Babbitt wondered if state lands with important habitat could be traded for BLM lands which had the potential for real estate development. This would put important natural resources under federal protection while giving the state more commercially valuable lands.

1985 MOU Between Arizona and the BLM

Babbitt gained an ally for his land exchange strategy when Dean Bibles was appointed the Arizona Director of the BLM in July 1982. But there were still some issues they needed to resolve. Almost all of Arizona’s state lands were leased to ranchers for livestock grazing, and ranchers whose state grazing leases would be affected by land exchanges could file protests.

On March 12, 1985, the BLM and State Land Department addressed this issue by signing a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to facilitate the exchange of lands between the two agencies. It addressed the concerns of state grazing lessees by stating that, “The exchange should not interfere with ranching operations.”

But the MOU had other clauses that conflicted with that promise. It included a caveat, for example, that said, “Unless the land is to be dedicated to a use that would preclude grazing.” And it stated that one of the primary purposes of the proposed exchanges was to “protect, wilderness, wildlife habitat, recreation and other public values.”

Furthermore, it stated the obvious fact that the MOU was subject “to the laws of the United States.” This included FLPMA, which required the BLM to manage livestock grazing in the public interest and prohibit it where it was inappropriate. Arizona’s state grazing lease lands were notoriously overgrazed, so how could the BLM allow inadequate grazing management to continue on the state lands it acquired in exchanges, as this would violate the objectives of the MOU and federal law? These contradictions were waived off by proponents of the land exchanges by explaining that the state grazing leases inherited by the BLM would only be honored until they expired, which would be no longer than 10 years – the term of a state grazing lease.

Subsequently, the BLM and the State Land Department began to conduct some land exchanges along the San Pedro River, and elsewhere in Arizona, wherein the BLM acquired lands with existing state grazing leases.

At the same time, Tenneco had put their San Pedro lands up for sale. Arizona conservationists asked Bibles to have the BLM conduct an exchange to acquire them. He offered Tenneco some commercially valuable BLM land but the company said it wanted cash. A three-party deal was subsequently worked out, with Babbitt’s help, wherein a real estate developer paid Tenneco $30 million for the land, and then traded 43,372 acres of it for about 41,000 acres of BLM desert land west of the White Tank Mountains near Phoenix. Bibles considered this acquisition, which brought a 30-mile long stretch of the San Pedro River into public ownership, the most important land acquisition the BLM had ever done.

After the San Pedro exchange was officially completed in the spring of 1986, the BLM announced they were keeping the acquired lands closed to the public until they could complete a natural resources inventory, and draft a management plan using the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) public planning process.

Arizona-Idaho Conservation Act of 1988

During this time Arizona conservationists were also promoting federal legislation that would officially designate the newly acquired BLM land along the San Pedro as a riparian preserve. The first bill to create the SPRNCA passed the U.S. House of Representatives in August 1986. It was sponsored by Tucson’s Republican Rep. Jim Kolbe and had strong support from Arizona’s congressional delegation. Conservationists wanted the acquired land to be transferred to the USFWS so it could be managed as a wildlife refuge. But political opposition forced that proposal to be dropped. So, instead, they pushed for a prohibition on livestock grazing in order to ensure that the local BLM officials would not consider grazing to be an appropriate multiple use in a riparian area. That also ran into opposition, so they agreed to a 15-year moratorium on grazing. But even after these political compromises were made, the bill was opposed in the Senate, primarily by Sen. Malcolm Wallop, R-Wyo., who was a rancher, and Sen. James McClure, R-Idaho. They objected to the grazing moratorium and the use of the word “riparian” in the bill. The bill was withdrawn in October by Arizona’s Democrat Sen. Dennis DeConcini.

The bill to create the SPRNCA was reintroduced in 1987 and passed the House again. But the Reagan administration actively opposed the bill’s grazing moratorium, so it got stuck in the Senate again. The grazing moratorium was also opposed by the National Cattlemen’s Association because, according to them, it would set “an unfortunate and unnecessary precedent” on BLM lands.

The creation of the SPRNCA had to wait until Congress passed an omnibus public lands bill called the Arizona-Idaho Conservation Act of 1988. This bill dropped the 15-year grazing moratorium along the San Pedro but said the BLM could only allow those multiple uses that “will further the primary purposes for which the conservation area is established.” It also expanded the SPRNCA’s official boundaries to include adjacent BLM lands recently acquired in exchanges with the State Land Department, thereby increasing the conservation area to about 56,431 acres. And it authorized the BLM to conduct land further exchanges with the state, or make purchases from willing private landowners, in order to help acquire inholdings within the new SPRNCA boundaries and create a consistent buffer strip along the river.

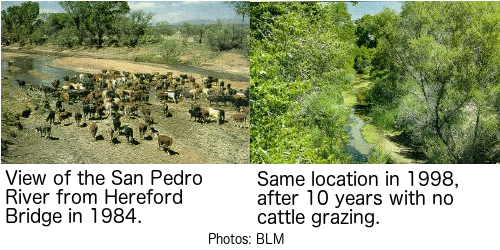

The San Pedro was the last major undammed river in the arid Southwest, and home to more than 315 species of birds, 82 types of mammals, and 45 kinds of reptiles and amphibians. It had been degraded by years of livestock grazing, but the ecological building blocks were still there and desert riparian areas had shown an ability to recover after grazing was ended.

1989 BLM San Pedro River Riparian Management Plan

The BLM had started working on a riparian management plan in 1987 for the land acquired through the Tenneco exchange, and had released a draft for public comment in June 1988. The law that created the SPRNC was passed after that, in November, and it raised some issues that needed to be addressed in the BLM’s final riparian plan. First of all, the new legal requirement to allow only those uses that protected and enhanced the riparian area meant that the final version of the plan needed to prohibit livestock grazing. (The BLM had already let a private grazing lease they had inherited with the acquisition of the Tenneco lands expire.)

But the final San Pedro River Riparian Management Plan decision issued in August 1989 failed to prohibit livestock grazing. Instead, it said “BLM does not regard livestock grazing to be incompatible with the continued existence of the riparian ecosystem,” and a “decision was made” to stick with the political compromise that had been considered in Congress to implement a 15-year grazing moratorium, after which the possibility of grazing would be “re-evaluated.”

The riparian plan also failed to address the status of the former state lands that had been included in the SPRNCA, because local BLM officials arbitrarily decided to address their management in the upcoming Safford District Resource Management Plan (RMP). (The Safford District is now just a field office in the BLM’s Gila District.)

The Arizona Cattle Growers’ Association had opposed the plan’s 15-year grazing moratorium, and so had the local Cochise-Graham Cattle Growers’ Association. But this was a time of increasing public awareness in Arizona about the importance of protecting riparian habitat. Local conservationists were warning that more than 90% of the state’s original riparian areas had been destroyed, altered, or degraded, while at least 75% of the state’s wildlife species depended on riparian areas for some portion of their life cycles. And they pointed out that five of Arizona’s 32 native fish species were no longer found in the state, and many of the remaining ones were endangered or threatened.

The Commission on the Arizona Environment had responded to this popular interest in riparian area protection by hosting a large public conference in Prescott during the summer of 1988. The attendees produced recommendations to protect riparian habitat, and Arizona Governor Rose Mofford subsequently issued Executive Order 89-16, Streams and Riparian Resources in June 1989. (She followed it up with Executive Order 91-6, Protection of Riparian Areas in 1991.)

1992 BLM Safford District Resource Management Plan

The Arizona BLM issued a partial decision for their Safford District RMP in September 1992. The only mention of the former state lands in the SPRNCA was a note on page 13 explaining they had convinced a rancher who was grazing some of them to withdraw his protest over “the language used to describe grazing lands that are within the boundary” of the SPRNCA that had been included in the RMP’s accompanying Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), which is where the management prescriptions approved by the decision were described in detail.

The EIS addressed the former state lands on page 21. First of all, it stated that the former stated lands amounted to 6,521 acres – not the previous estimate of 8,763 acres. The BLM also said that the inherited state grazing leases which were associated with these lands had to be honored, as per the 1985 MOU. But it also said that livestock grazing would only be allowed to continue on the 6,521 acres “for the term of these leases.” (The BLM, however, has continued to reauthorize grazing on these lands despite the fact that all of the preexisting state leases expired in 1996.)

The degree to which the affected state grazing lessees believed the MOU still applied to their situations is very questionable. According to State Land Department records, they signed their 10-year grazing leases in 1986, the same year the initial San Pedro land exchange with Tenneco was completed. It was well known that the BLM had acquired the land to manage it as a riparian preserve. Moreover, the first bill to create the SPRNCA was introduced in Congress in 1986, and it included the 15-year grazing moratorium and an intention to expand the project outside of the boundaries of the original land exchange. The lessees must have expected that their former state grazing leases would probably eventually be terminated.

The EIS also promised that the BLM would “intensively manage” the 6,521 former state acres and implement grazing allotment management plans for the “protection of the riparian values of the National Conservation Area.” This promise was important because one of the BLM grazing allotments that had been created from the state lands included 2.5 miles of desert riparian habitat along the lower Babocomari River, a tributary of the San Pedro.

The BLM included no other information about the SPRNCA’s former state lands in the EIS or RMP.

The Safford District’s RMP decision in 1992 was only a partial one because the BLM said several controversial issues that needed to be “deferred.” One of these issues resulted from a clause that was included in the 1989 San Pedro River Riparian River Management Plan that said, “Lands may also be obtained outside the boundaries for the protection and enhancement of the resource values found outside the EIS area.” The official boundaries of the SPRNCA included the upstream stretches of the San Pedro south of Interstate 10. Conservationists wanted the BLM to acquire more riparian habitat along the downstream stretches of the river, north of I-10 to its confluence with the Gila River.

In 1988, however, the Arizona Supreme Court had put a stop to the State Land Department conducting exchanges with the BLM. The court had issued a ruling that the Arizona Legislature needed to amend the Arizona Constitution to give the State Land Department the authority to make land exchanges, even though Congress had authorized the state to make them in 1936. Until the legislature passed that amendment, the court said, state lands could only be acquired by purchase at a public auction. Subsequently, the BLM’s plan to acquire more riparian habitat along the San Pedro north of I-10 had to rely upon the purchase of private land from willing sellers.

Local landowners reacted angrily when the BLM released a map in June 1992 that showed the private parcels it wanted to acquire along that part of the San Pedro. Subsequently, Arizona BLM Director Les Rosenkrance suspended the initiative and explained in the partial 1992 RMP decision that a new planning process had been initiated with local landowners to resolve the conflicts.

In 1994 Rosenkrance issued another partial decision for the Safford District RMP regarding the issues that had been deferred from his 1992 decision. In regards to the acquisition of land along the San Pedro north of I-10, he said the BLM was adopting a new review process agreed to by the local landowners. It had the goal of determining if the conservation of riparian resources could be “accomplished without acquiring title to the land.” This effectively put an end to the BLM’s efforts to acquire more land along the San Pedro outside the boundaries of the SPRNCA.

2018 SPRNCA Draft Resource Management Plan

The SPRNCA Draft Resource Management Plan (DRMP) and accompanying EIS the BLM’s Gila District released in June 2018 included a new estimate of the size of the former state grazing lands. It said they comprised about 7,030 acres, not the previously estimated 6,521 acres. The BLM said that improvements in GIS technology likely caused the difference.

The DRMP’s biggest surprise, however, was the BLM’s proposal to increase livestock grazing on the SRPNCA to include 26,450 acres – an increase of more than 375%! They proposed to authorize up to 3,363 additional animal unit months (AUMs) on these new grazing lands – about 280 head of cattle yearlong. The BLM said the areas would somehow be “identified” for grazing on the SPRNCA’s Chihuahuan Desert uplands, but livestock would continue to be prohibited in its riparian areas, with the exception of the lower Babocomari River. They also said that grazing would not be allowed to begin on these new areas until fences were built to prevent cattle from accessing the river, but they failed to mention that the taxpayers would probably have to pay for them. The permits to graze these areas, they said, would be made available as per 43 CFR § 4110.4-1, meaning they would be gifted “to qualified applicants at the discretion of the authorized officer.” These new grazing lands would be added to the existing 7,030 acres of former state grazing lands that the BLM proposed to continue to graze, even though the inherited state grazing leases had expired in 1996.

The DRMP didn’t include any specific livestock grazing management prescriptions, but it said the BLM’s Arizona Standards for Rangeland Health and Guidelines for Grazing Administration would apply to all grazing on the SPRNCA. These standards and guidelines (S&Gs) were implemented by the Arizona BLM in 1997 as a result of the public lands grazing regulatory reform initiative known as Rangeland Reform ’94, promoted by Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt during the administration of President Bill Clinton.

But the DRMP’s EIS included few other details about livestock grazing on the SPRNCA, despite that fact that the BLM had never completed a NEPA analysis for the former state grazing lands, and was proposing to significantly increase grazing.

History of BLM’s Management of Grazing on the SPRNCA

As described above, according to the EIS for the Safford District RMP, the state grazing leases inherited from the former state lands were supposed to be “recognized” for no longer than their original “term.” However, the BLM has continued to allow grazing on them and has made few livestock management changes to comply with the primary purpose of the SPRNCA.

The EIS also said that allotment management plans “would be prepared” for the four associated BLM grazing allotments – which are the Babocomari, Lucky Hills, Brunckow Hill, and Escapule (now called Three Brothers) allotments. But no NEPA analyses have been completed for any of them, and the only allotment management plan (AMP) that appears to have been implemented was the Brunckow Hill AMP in 1990.

Instead, in 1996 the BLM started working with the local office of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) to implement a coordinated resource management plan (CRMP) for the Lucky Hills Ranch, which includes the BLM’s Lucky Hills allotment. But a CRMP isn’t the equivalent of an AMP. CRMPs are typically used to identify livestock management plans for ranches that are a mixture or private, state, and federal land. Ranchers are required to complete them in order to acquire financial assistance from the NRCS. They typically aren’t drafted using the NEPA public planning process, and the BLM can’t enforce compliance with the terms of a CRMP. Nor is the BLM typically the lead agency in the drafting of a CRMP.

The Lucky Hills Ranch CRMP was completed in 1997. It prescribed a rotational grazing system for the ranch, with each pasture to be grazed for about two months. But it also allowed a maximum annual upland forage utilization rate of up to 60%, which is much too high to be appropriate for a nature preserve in a desert.

It’s unclear if the Lucky Hills Ranch CRMP was initiated by the BLM to try and comply with the 1992 RMP, or if it was a response to the lawsuit that was filed against them on January 3, 1996, by the Center for Biological Diversity. The lawsuit accused the agency of failing to comply with the legal requirement to consult with the USFWS about the livestock grazing they were permitting in endangered species habitat on BLM lands in southeast Arizona. The BLM quickly initiated ESA Section 7 consultation with the USFWS and in May sent them a Biological Evaluation (BE) that provided some descriptions of the existing livestock management situations on the agency’s grazing allotments in the region, including the four grazing allotments on the SPRNCA.

The USFWS responded to the BLM with a legally binding Biological Opinion (BO) regarding the agency’s grazing management in the region on September 26, 1997. The BO incorporated several mitigation measures the BLM had promised to implement in order to comply with the Endangered Species Act, and some of them applied to the SPRNCA allotments.

Some of the mitigation measures were quite specific. In order to protect the endangered Huachuca water umbel, a semi-aquatic plant, the BLM promised to remove trespass cattle from the SPRNCA as soon as possible and maintain the fences that were supposed to keep them out. Furthermore, they promised to work with the lessee to exclude livestock from the small stretch (about 0.3 mile) of the San Pedro River found on the Brunckow Hill allotment. They also renewed their pledge to complete AMPs for the SPRNCA’s four allotments, and promised AMPs would be completed for the Babocomari and the Lucky Hills allotments by 1998, for the Brunckow Hill allotment by 1999, and the Three Brothers allotment by 2000.

The BLM also made a commitment to some mitigation measures that were more general. They promised to prohibit the use of chemical herbicides to kill brush in the riparian habitat along the San Pedro and Babocomari rivers. But since 1997 the aerial spraying of a herbicide called Spike, which contains tebuthiuron, to kill brush to grow more grass for cattle has occurred on at least three of the four ranches using the grazing allotments in the SPRNCA. It appears it was used on upland pastures, away from riparian areas, but the EPA has issued warnings that tebuthiuron has a great potential for groundwater contamination, and due to its high water solubility and long persistence in the soil, it can be carried downstream in storm runoff. Another danger is that, even though it targets woody vegetation, it’s still toxic to a lot of herbaceous plants – including some grasses. This means the land can be practically denuded, destroying all wildlife habitat, and stay that way if there’s drought after it’s applied. This is especially a problem because it usually takes multiple applications to kill woody plants. These herbicide treatments were subsidized with government assistance, including unknown amounts of money from the BLM’s Healthy Lands Initiative.

Furthermore, the Arizona BLM’s new S&Gs had recently been implemented, so the agency also promised to “adhere” to the S&Gs on all four of the allotments in the SPRNCA. And they promised to begin submitting annual reports to the USFWS about their progress in implementing these measures.

But the BLM failed to keep most of their other promises to the USFWS. For example, according to the DRMP they have not completed any new AMPs for the four SPRNCA allotments. And the DRMP says the BLM also hasn’t completed S&Gs assessments for them, although it says that “partial assessments” were completed for the Brunckow Hill, Three Brothers, and Lucky Hills allotments.

A review of those three partial assessments provides more disturbing information. The Brunckow Hill allotment’s 2008 S&Gs assessment said that, “There are no standing interior cross-fences that delineate private/public land boundaries crossing this San Pedro River segment on the allotment.” In other words, the BLM hadn’t kept their promise to exclude cattle from the allotment’s small BLM-owned portion of the San Pedro River. (The Analysis of the Management Situation Report that accompanied the DRMP says the fences were in place by 2012.)

It also said that a proper functioning condition (PFC) assessment was completed on this stretch of the river in 2006. (PFC assessments are widely used to help determine the ecological health of riparian areas.) The Brunckow Hill PFC assessment showed this stretch of the river was Functional At Risk with a downward trend. Despite these issues, the allotment’s S&Gs assessment said the Riparian-Wetland Sites standard was being met. This wasn’t mentioned in the DRMP. The assessment also said the Upland Sites standard was being met, even though the BLM had monitored just one key area on the entire allotment.

The BLM also used only one key area in the Three Brothers allotment’s 2008 S&Gs assessment to determine it was meeting the Upland Sites standard. The 2009 S&Gs assessment for the Lucky Hills allotment said just two key areas were observed to make the determination that the Upland Sites standard was being met. The Three Brothers and the Lucky Hills assessments both made the dubious claim that, because the allotments were meeting the Upland Sites standard, they were automatically meeting the Desired Resource Conditions standard. This was not included in the DRMP.

Brookline Ranch

As for the Babocomari allotment, which is part of the Brookline Ranch, and includes a stretch of the Babocomari River, the DRMP said that no “formal” S&Gs assessment had been completed. However, the BLM had released a proposed decision on August 4, 2000, to issue the initial regular 10-year BLM grazing lease for the allotment, as they had been using annual grazing authorizations since the inherited state lease had expired in 1996. The proposed decision included no details about the livestock management situation on the allotment, but it claimed that an S&Gs assessment had recently been completed that showed “resource conditions meet applicable standards” and “no further changes in the current operation are required at this time.” This assessment was later revealed to be just a short form evaluation.

The BLM’s proposed decision was protested by Forest Guardians because the agency hadn’t engaged the NEPA public planning process to analyze allotment-specific management alternatives, as required by the Rangeland Reform ’94 regulations. But the BLM rejected the protest in a final decision issued on October 13, 2000. They claimed that an allotment-specific NEPA analysis wasn’t required, because their previous regional Eastern Arizona Grazing EIS sufficed to meet the NEPA requirement, even though it was completed before the creation of SPRNCA, and didn’t include any information about the Babocomari Allotment.

The NRCS had quietly completed a CRMP for the Brookline Ranch in 2006. Its introduction section included a false claim that the ranch’s owner often repeated. It stated that the state grazing lease the BLM had inherited when they acquired the allotment was the result of a land exchange that occurred in 1988, after the ranch’s owner had acquired the grazing lease on November 3, 1988. But an examination of public records shows that the Babocomari land exchange occurred in 1987, which means the ranch’s previous state grazing lessees had agreed to it before the current lessee acquired it, and he would have known about the prior exchange when he bought the lease from them. In fact, it would have been impossible for the exchange to have occurred after November 1988, because the State Land Department had suspended exchanges in September 1988 due to the Arizona Supreme Court ruling.

Furthermore, after Congress created the SPRNCA in late November 1988, the Babocomari allotment’s grazing lessee contacted Arizona Congressman Jim Kolbe’s office to express concern about the future of his BLM lease on the former state land within the newly designated riparian preserve. BLM Safford District Manager Ray Brady’s response to Rep. Kolbe’s inquiry documented that the exchange had occurred earlier, and that the Babocomari lessee knew the situation when he bought the lease. The letter also included a promise that the BLM would continue to honor the Babocomari allotment’s inherited state lease. This was about five months before the completion of the San Pedro River Riparian Management Plan, which shows that local BLM officials were already determined to refuse to consider full compliance with Arizona-Idaho Conservation Act in regards to the SPRNCA’s former state lands

Instead of ending grazing, as was being proposed for the rest of the SPRNCA, the BLM’s response to Kolbe said the stretch of the Babocomari River found on the allotment would be protected through the implementation of an AMP. The BLM did, indeed, draft a Babocomari AMP in 1990. It said that, “The highest priority will be given to the riparian corridor that runs about 3 miles through the lease.” This would be, “accomplished by building an exclosure fence excluding the riparian area from grazing.” But it apparently was never implemented, as livestock aren’t excluded from the Babocomari River, and the DRMP didn’t indicate than any AMPs were completed for the SPRNCA’s allotments.

The 2007 Brookline Ranch CRMP said the allotment would be divided into eight pastures and a best-pasture, deferred rotation grazing system would be used. The 2,550 pasture River pasture, which included the Babocomari River and the BLM’s allotment, could be used any time of the year, although it would “rarely” be used during the growing season from late May through mid-September, but it would be grazed “some part of these months every 4th year or so.”

This plan is similar to the one the BLM very briefly described for the Babocomari allotment in the biological evaluation they submitted to the USFWS in 1996. By all accounts, the existing lessee has significantly improved the condition of the Babocomari allotment from what it was when he acquired the original state lease. But his success should be measured by more than just how much the allotment has improved. It should consider if, after 30 years, the allotment is currently meeting the wildlife habitat objectives of a riparian nature preserve, because the allotment is part of the SPRNCA – not common rangeland.

The continued grazing in the Babocomari River’s riparian habitat is a cause for concern. According to the CRMP, the lessee has typically limited it from May through September. But April through October is the summer growing season in southern Arizona. And the fact that the BLM’s Babocomari allotment grazing lease only permits up to 15 head of cattle yearlong is misleading. The Brookline Ranch is a mixture of private, state, and BLM land, so the ranch’s entire herd is about 100 head of cattle. The CRMP said the River pasture is 2,550 acres, which means there could be about 25 head per acre in the pasture, provided they were evenly distributed – which they wouldn’t be. This could put a lot of cattle in the allotment’s riparian areas. Furthermore, the CRMP didn’t include any riparian utilization standards and allowed a maximum annual upland forage utilization rate of up to 50%, which is too high for the SPRNCA.

The USFWS issued an update to their 1997 biological opinion on the BLM’s local grazing program on May 21, 2012. It included mandatory new conservation measures the BLM was required to implement in order to protect the endangered Southwestern willow flycatcher, a bird that depends upon riparian habitat. Livestock were required to be excluded from suitable or potential flycatcher habitat from April 1 through October 30, and the consumption of cottonwood and willow tree shoots reachable by cattle could not exceed 30 percent. The Babocomari and Brunckow Hill allotments were identified as having flycatcher habitat.

The Brookline Ranch CRMP does not comply with these new requirements. It allows grazing along the Babocomari River in April and October, along with any other time it was deemed necessary by the grazing lessee. It also allows an annual forage utilization amount that was 67 percent higher than 30 percent. There was no indication in the DRMP that the ranch’s management plan was revised to comply with these new requirements.

The USFWS had based their 2012 biological opinion upon the descriptions the BLM had given them of the ongoing livestock management situations on the Gila District’s grazing allotments. Those descriptions raise questions.

In regards to the Babocomari allotment, Table 4 in the 2012 BO indicates that the BLM told the USFWS that there was a riparian exclosure on Babocomari River in the Babocomari allotment – but there isn’t, just a riparian pasture that’s periodically grazed. And the BO said the BLM claimed the allotment was meeting the Riparian-Wetland Sites standard. But a PFC assessment was conducted for the Babocomari River on the ranch’s BLM allotment in October 2013 found that most of it was Functioning At Risk with a downward trend due to several factors, including watershed condition, unauthorized livestock grazing, and upstream land use. The assessment documented that; “bank and floodplain vegetation in the lower reach showed evidence of disturbance from livestock trampling and foraging. Bank extensions had been trampled to the extent that plants and root mats were inadequate to support PFC, cattle trailing appeared to have caused cut-off channels, and trampling had further loosened soil where cover was poor. Many young cottonwoods were in a shrubby form, indicating ongoing and heavy foraging.” The assessment didn’t identify if the damage had been caused by cattle that belonged to the Babocomari lessee, or by trespass cattle. But the grazing that’s permitted in this riparian area could not have improved the situation.

Also, Table 3 in the BO showed the Babocomari allotment was meeting the Uplands Sites and Desired Resource Conditions standards. But according to the DRMP, no formal S&Gs assessment has ever been completed for the Babocomari allotment.

Regarding the small stretch of the San Pedro River on the Brunckow Hill allotment, the 2012 BO said it was meeting the Riparian-Wetland Sites standard, but according to the DRMP, no S&Gs assessment of this particular riparian area has ever been completed.

The information the BLM provided to the USFWS about the Three Brothers allotments is also contradictory. The DRMP said the 2008 S&Gs assessment found the allotment was meeting the Upland Sites standard. But Table 3 in the 2012 BO said an assessment had not been completed, and Table 2 showed that most of the allotment was in poor condition with a static trend.

The bottom line is that the BLM has never completed the required NEPA analyses, thorough S&Gs assessments, and allotment management plans for the four active grazing allotments in the SPRNCA.

San Pedro River Contaminated With E. coli

The bacterium Escherichia coli is a dangerous pathogen that has been detected in the San Pedro River below the mouth of the Babocomari River, and the primary source is cattle feces. This was determined by a $265,551 study funded by Water Quality Improvement Grant (WQIG) #12-003 from the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ). The grant also funded the creation of a watershed improvement plan to address the problem. The resultant plan called for the construction of erosion control structures in the Babocomari River watershed, the source of most of the E. coli contamination, in order to reduce contaminated runoff downstream into the San Pedro River. These remediation measures were implemented using $224,628 provided by WQIG #18-006.

All of the management alternatives in the DRMP included the water management goal to, “Reduce or prevent contamination of surface and groundwater nonpoint source pollution to meet state requirements.” But that didn’t address the more stringent federal requirement to manage the SPRNCA as a riparian preserve.

In fact, on page 2-13 of the DRMP Appendices the BLM admitted that allowing cattle grazing in the SPRNCA “may increase” E. coli contamination in the rivers. It also said that cattle grazing “may be constrained” if “water quality impacts exceed acceptable levels.” But on page 3-12 they admitted that ADEQ had already found that E. coli levels exceeded allowable levels in the San Pedro River between the mouth of the Babocomari River and downstream to Dragoon Wash. Apparently, however, they believed the E.coli contamination could somehow be eliminated while continuing to authorize grazing along the Babocomari River.

Trespass Cattle

The BLM’s history of proficiency, or lack thereof, in keeping trespass cattle out of the San Pedro and Babocomari rivers is a persistent problem. The problem was so bad in 1996 that a trespass cattle roundup was the first mitigation measure they implemented in response to the lawsuit that was filed against them by the Center for Biological Diversity. It was mentioned again in the 2012 biological opinion and was still a problem in 2013 when the PFC assessment for the lower Babocomari River was completed. And by many accounts, it’s still an issue. But despite the persistence of this problem, there was only one reference to trespass livestock in the DRMP, and it only said that sometimes it happens when gates are left open by recreationists.

Summary

The BLM’s history of managing livestock on the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area only matters if grazing is going to be permitted to continue. The law that created the SPRNCA said only those uses that “will further the primary purposes for which the conservation area is established” shall be allowed. It explained the SPRNCA was established, “In order to protect the riparian area and the aquatic, wildlife, archeological, paleontological, scientific, cultural, educational, and recreational resources of the public lands surrounding the San Pedro River in Cochise County, Arizona.”

Updates

During the public comment period in 2018 for the BLM’s DRMP, the former director of the Arizona BLM, Dean Bibles, submitted comments that severely criticized the proposal to continue and increase livestock grazing. He pointed out that the SPRNCA was not supposed to be managed for multiple use, but as a nature preserve, and that “there was no intention and therefore no commitment to continue grazing after the outstanding state leases terminated.”

On February 27, 2019, I visited the river pasture on the BLM’s Babocomari grazing allotment and found that it was being degraded by livestock.

On April 26, 2019, the BLM’s Tucson Field Office released their Proposed SPRNCA RMP/Final EIS. They had dropped the scheme to increase grazing on the SPRNCA by about 375%, but proposed to allow existing grazing to continue on the 7,030 acres of former state lands, including the lower Babocomari River, in violation of the law that created the SPRNCA.

On July 30, 2019, the BLM issued its final decision on their Resource Management Plan (RMP) for the SPRNCA. They used circular logic to resolve the protests of their proposal to allow livestock grazing to continue on 7,030 acres of former state land. They promised, however, to finally implement appropriate livestock management on the SPRNCA’s grazing allotments using a process that, “will have a public involvement component.”

On April 7, 2020, a coalition of environmental groups filed a federal lawsuit against the BLM’s decision to continue to permit livestock grazing in the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area.

During the March 23, 2021, meeting of the Cochise County Board of Supervisors, District 1 Supervisor Tom Crosby stated that he believed the creation of the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area was “unconstitutional.”

On May 20, 2021, the Arizona BLM’s Tucson Field Office released draft Land Health Evaluations for the active grazing allotments in the SPRNCA which indicated they intended to allow livestock grazing to continue on them.

On April 29, 2022, the Arizona BLM’s Tucson Field Office released a preliminary EA and final Land Health Evaluations for the active grazing allotments in the SPRNCA, which confirmed their intention to continue grazing them.

On August 2, 2022, a settlement agreement was approved in federal court that sent the BLM back to its planning process to reconsider the impacts of livestock grazing on the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, and update the 2019 RMP if their review found that grazing should be discontinued. The settlement resolved the litigation filed against the BLM by conservationists in April 2020.

On December 21, 2022, the BLM issued a Finding Of No Significant Impact (FONSI) wherein they claimed their review of their decision to renew grazing leases in the 2019 RMP, as required by the 2022 legal settlement, found there was no reason to make any changes. On the same day they issued the FONSI, the BLM released proposed decisions and an environmental assessment (EA) to renew the leases, as part of the NEPA planning process they had initiated in April.

On April 7, 2023, the BLM dismissed the protests they had received in response to their December 21, 2022, proposed decisions for the four SPRNCA grazing allotments, and made them final decisions. They were subsequently appealed by the protestors to the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Office of Hearings and Appeals.

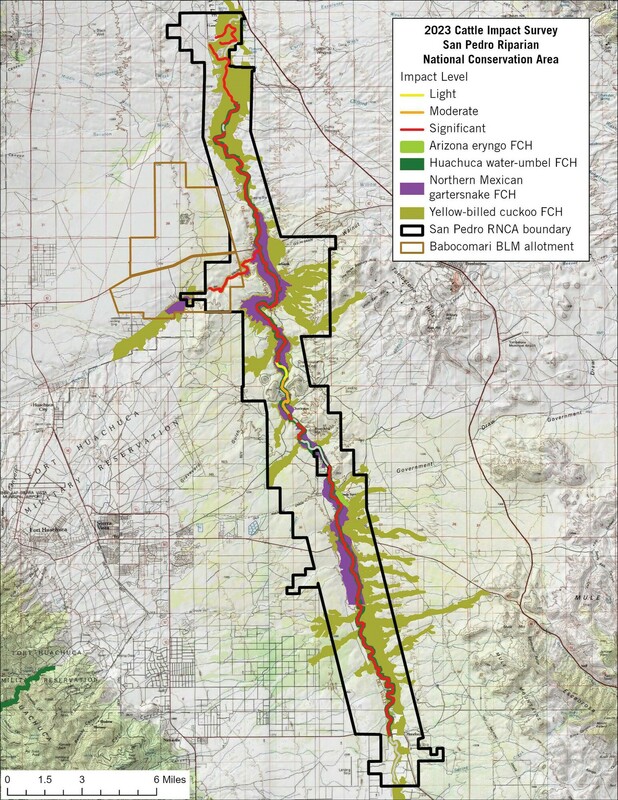

On April 10, 2023, the Center for Biological Diversity released a survey which showed that cattle are damaging nearly every river mile of San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area.

In May, 2023, the BLM released documentation of six recent cooperative range improvement agreements (CRIAs) to help fund projects to keep cattle from neighboring BLM grazing allotments out of the SPRNCA, and to create SPRNCA boundary fences within its active grazing allotments:

Babocomari Allotment CRIA, 2023

Brunckow Hill Allotment CRIA, 2023

La Roca Allotment CRIA, 2022

Q. Miller Allotment CRIA, 2021

Q. Miller Allotment CRIA, 2023

Spring Creek Allotment CRIA, 2022

On October 20, 2023, the Western Watersheds Project submitted a Motion for Summary Judgement to the U.S Department of the Interior’s Office of Hearings and Appeals asking that the BLM’s April, 2023, final decisions to continue livestock grazing in the SPRNCA be summarily reversed, and for grazing to be finally eliminated in the SPRNCA.

On January 29, 2024, the BLM issued a decision memo to approve the construction and maintenance of approximately 93 miles of livestock fences to protect the SPRNCA.