Republicans have launched the biggest attack on America’s public lands since President Ronald Reagan gave political legitimacy to the Sagebrush Rebellion by appointing James Watt Secretary of the Interior in 1981.

Earlier this year they passed nonbinding budget resolutions in the U.S. Senate and House that suggested privatizing public lands by giving them to the states. And Republican legislatures in several Western states have passed measures promoting the distribution of federal lands to the states. This new assault is being supported by the American Lands Council, with support from the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a conservative think tank supported by the Koch brothers. ALEC recently released a disingenuous report which claims the states would be better environmental stewards of the Western public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Forest Service, while simultaneously increasing their economic production.

Smokey Bear Was Wrong

The growing frequency of catastrophic wildfires on Western public lands is the cornerstone of Republican claims that the states would be better environmental stewards. This isn’t a fair criticism of federal land management, however, because American forestry suffered from bad science until relatively recently. Ecologists now understand that many ecosystems are fire-adapted, and depend upon periodic low-intensity wildfires to maintain their health.

But for many years land managers used Smokey Bear to promote the idea that all forest fires were bad. The resultant suppression of natural fire regimes is the primary reason that many forests on public lands are now unnaturally dense with trees, making them more susceptible to catastrophic fires. Higher temperatures and lower humidities from climate change are also contributing to the situation.

The most prevalent activity on Western public lands, however, is livestock grazing. The ALEC report claims there’s “ample evidence” that the states would be “superior” environmental stewards of public lands. But the Western states have very poor reputations when it comes to managing grazing on their state lands.

The Arizona State Land Department, for instance, manages approximately 9.2 million acres of State Trust lands and the vast majority of it is leased to ranchers for livestock grazing. The department does little to implement livestock management plans and the state’s grazing lands are widely considered to be in poorer shape than local grazing allotments administered by the BLM and Forest Service. In fact, the department has such a bad reputation in regards to livestock management that in the 1980s it willingly participated in land exchanges which traded hundreds of thousands of acres of environmentally sensitive state lands to the BLM because everyone understood that the federal agency would do a better job of protecting them. (And they have.)

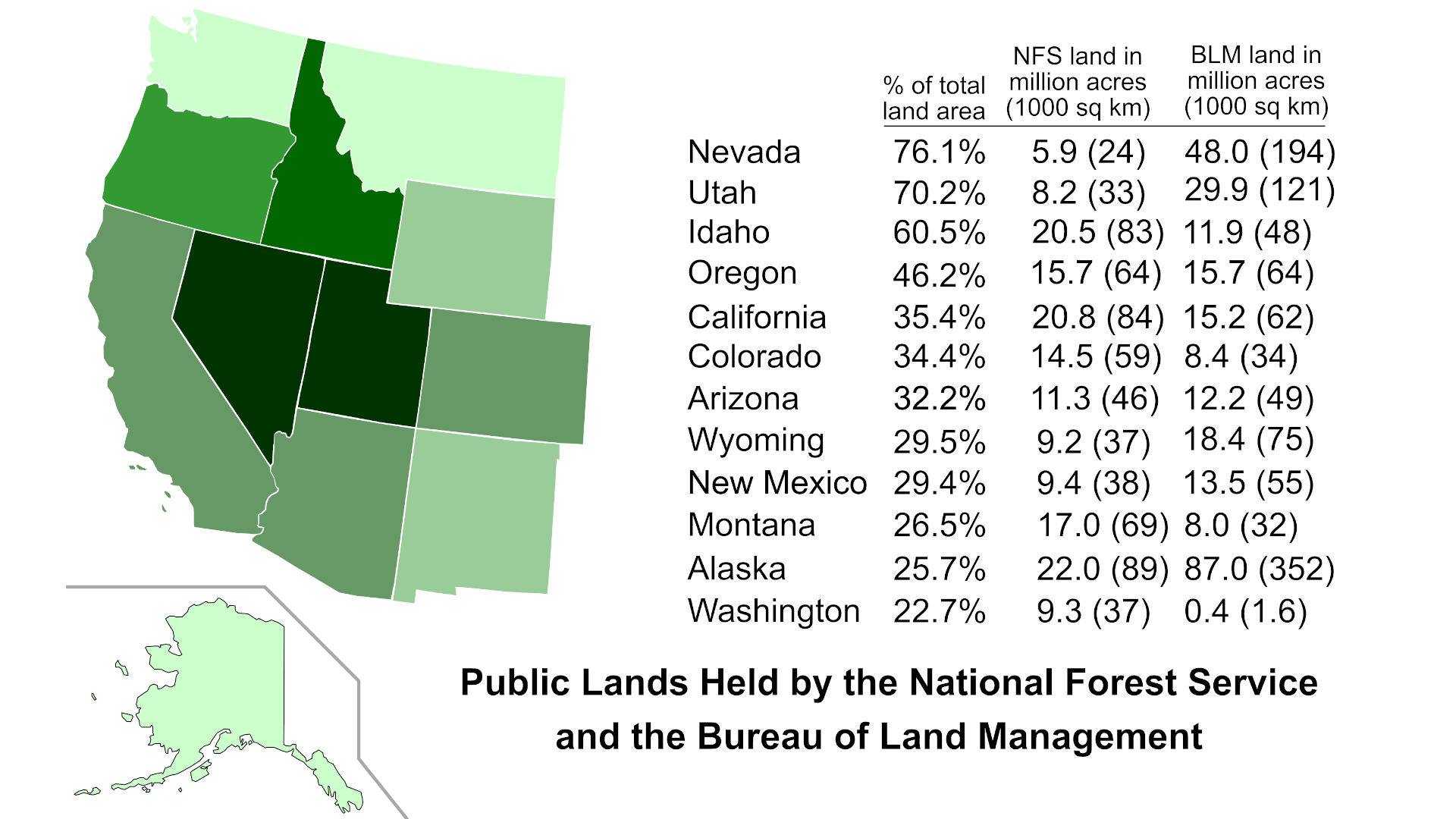

The other claim that proponents of privatizing public lands make is that economic production could be increased on them if they were given to the states. This argument begins with a complaint that it isn’t fair for the federal government to own so much land in the West. They point to the fact that public lands comprise more than half of the land in three Western states, and at least a fifth of it in all of them, and this supposedly hurts the local rural economies.

According to ALEC, “The federal government’s control over so much land in the western states is inconsistent with America’s longstanding doctrine of the inherent equality of all states. This important principle is violated by allowing the eastern states jurisdiction over the vast majority of their lands but denying the same to the western states.” But the reason so much land in the Western states is still owned by the federal government is that nobody wanted it because it was too mountainous and/or dry.

The pattern of federal land ownership during the westward expansion from the original 13 colonies was set by the passage of the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. After the claims of local Native American tribes were extinguished, the government surveyed the land and sold it, except for some parcels that were given to the states to support public schools.

Special natural places on federal land began to be set aside when the Yellowstone Act of 1872 created Yellowstone National Park, the world’s first national park. The Forest Reserve Act of 1891 allowed federal land to be set aside to establish national forest reserves to preserve important watersheds by requiring controlled timber cutting. In 1905 the Forest Service was created to manage these lands, now called National Forests.

Those federal lands that weren’t set aside for the common good were still available to settlers. The Homestead Act of 1862 gave people the opportunity to obtain ownership of a parcel of federal land without having to buy it. All they had to do was live on the land and prove they had farmed it for five years. Despite these generous terms, only about 40 percent of the applicants succeeded in getting a land title because, by 1862, most of the unsettled lands were in the arid West and not suited for agriculture.

In 1946 the BLM was created to manage most of the land that hadn’t been set aside and was still owned by the federal government. President Herbert Hoover had proposed to deed these lands to the Western states in 1932, but they declined his offer, complaining that it would cost too much to manage them.

Commodity Producers Oppose the Multiple Use Doctrine

Attempts to privatize the West’s public lands aren’t new. For example, an editorial titled the Great Land Grab criticizing the idea was published in the newsletters of Arizona conservation groups in 1947. Today’s Republican assault against public lands is partly a reaction to the relatively recent successes that conservationists have had in getting long-standing environmental laws applied on most federal lands. They include the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960, National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1970, Endangered Species Act of 1973, National Forest Management Act of 1976, and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976. These laws changed the management of public lands by making commodity production just another use, instead of the dominant use that it was for many years. They defined a new multiple use doctrine, wherein all activities shouldn’t be permitted on all public lands, and the objective of public lands management isn’t necessarily the maximization of commodity production – but to identify the appropriate mix of uses that are in the best interests of the general public. In other words, a fair and common sense strategy.

It’s taken many years of social activism and federal court cases filed by conservation groups to get things changed on the ground, and this struggle still continues in some localities. An example of the local political opposition these laws have faced is shown by the Clinton administration’s Rangeland Reform ’94 initiative to update public lands grazing regulations. The promulgation of these new rules took place many years after the laws they codified were passed by Congress.

Old school Westerners who were easily able to profit off public lands dislike the new ethical paradigm represented by the implementation of the multiple use doctrine. Ranchers holding federal grazing permits have been especially stubborn, as evidenced by the recent behavior of rancher Cliven Bundy in Nevada when the BLM attempted to enforce the law.

The Fossil Fuel Industry is Funding the Attack

This latest attack against public lands taps into this resentment, but the real impetus comes from deep-pocketed oil and natural gas producers. New hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling technologies have created a boom in fossil fuel exploration and production and the industry doesn’t like the federal environmental regulations that apply to their operations on public lands. Earlier this year, for example, Congressional Republicans introduced the Federal Lands Freedom Act, which proposes to give the states the power “to control the development and production of all forms of energy on all available Federal land.” Fossil fuel producers obviously think it would be easier for them to deal with state regulators, and they’re probably right about that. For instance, the primary reason Arizona Republican legislators supported the creation of the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) in 1986 was to allow the state to try and take over the enforcement of national environmental laws from the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), with the tacit understanding that state enforcement would be more lenient.

Public Lands Are a Treasure, Not a Burden

The argument that federal lands, as they are currently managed, are burden upon rural economies in the West needs to be closely examined. An often heard claim is that local governments with lots of public lands within their boundaries cannot collect sufficient tax revenue because federal lands are exempt from private property taxes. But in 1976 Congress also created the Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) program to provide payments to them to offset the lost tax revenue. Arizona, for example, received more than $30 million in PILT funds during the 2014 federal fiscal year.

A fair assessment of the economic production from public lands must take into account everything they produce. According to the Arizona Game and Fish Department, fishing in Arizona generates an estimated $831.5 million on equipment and trip-related expenditures annually, while hunters account for an additional $126.5 million in retail sales. Watchable wildlife activities, the agency says, generate another $1.5 billion. Together they generate more than $115 million in state tax revenue. The Outdoor Industry Association says that all forms of outdoor recreation in Arizona generate $10.6 billion in consumer spending annually. A very large portion of these activities occur on Arizona’s public lands.

Less tangible benefits from public lands must also be considered. One of the original reasons for the creation of National Forests, for instance, was to help protect municipal watersheds. This continues to be important in the arid West where many cities, such as Phoenix, rely upon upstream reservoirs for their water supplies.

Public lands also harbor reservoirs of biodiversity, and they are the foundation of the food chain that supports human life. Public lands will become increasingly important for preserving biodiversity because scientists say we have entered the Anthropocene Epoch in Earth’s history, wherein humans are having an unprecedented impact upon the planet. Climate change caused by the burning of fossil fuels, along with demands put upon natural resources by the growing human population, are combining to damage and destroy entire ecosystems. The millions of acres of undeveloped public lands in the West are the best hope for many American plant and animal species.

The Bottom Line

The existing multiple use doctrine allows for mining, logging, grazing, and drilling activities to occur on federal lands – but only where they are appropriate and only when they comply with environmental laws. This wise philosophy is the real target of the proponents of turning public lands over to the states. They want to go back to the not-so-distant bad old days, when commodity production monopolized public lands. They don’t have the support of the general public, as shown by the defeat of Proposition 120 in Arizona in 2012. This measure was placed on the ballot by the Republican-led legislature and called for the state to unilaterally declare it’s control over its federal public lands. It was soundly defeated, with 67.7% of the voters rejecting it. Privatizing public lands is just more right-wing Republican kookery.

Updates

On April 11, 2019, the U.S. Senate confirmed Pres. Trump’s appointment of former fossil fuels lobbyist David Bernhardt, who doesn’t believe there should be public lands, to be the Secretary of the Interior.

On July 16, 2019, the Trump administration confirmed plans to relocate most of the Bureau of Land Management’s headquarters staff from Washington, D.C., to the West by the end of 2020. The move was seen as a first step towards privatizing BLM lands, which are administered under the Department of the Interior.

On July 29, 2019, Interior Secretary Bernhardt appointed William Perry Pendley to be the acting director of the Bureau of Land Management. Like Secretary Bernhardt, Pendley believes that public lands should be sold off.