If you’ve ever been upset by encountering the ecological degradation caused by livestock grazing on public land, here are some suggestions for doing something about it.

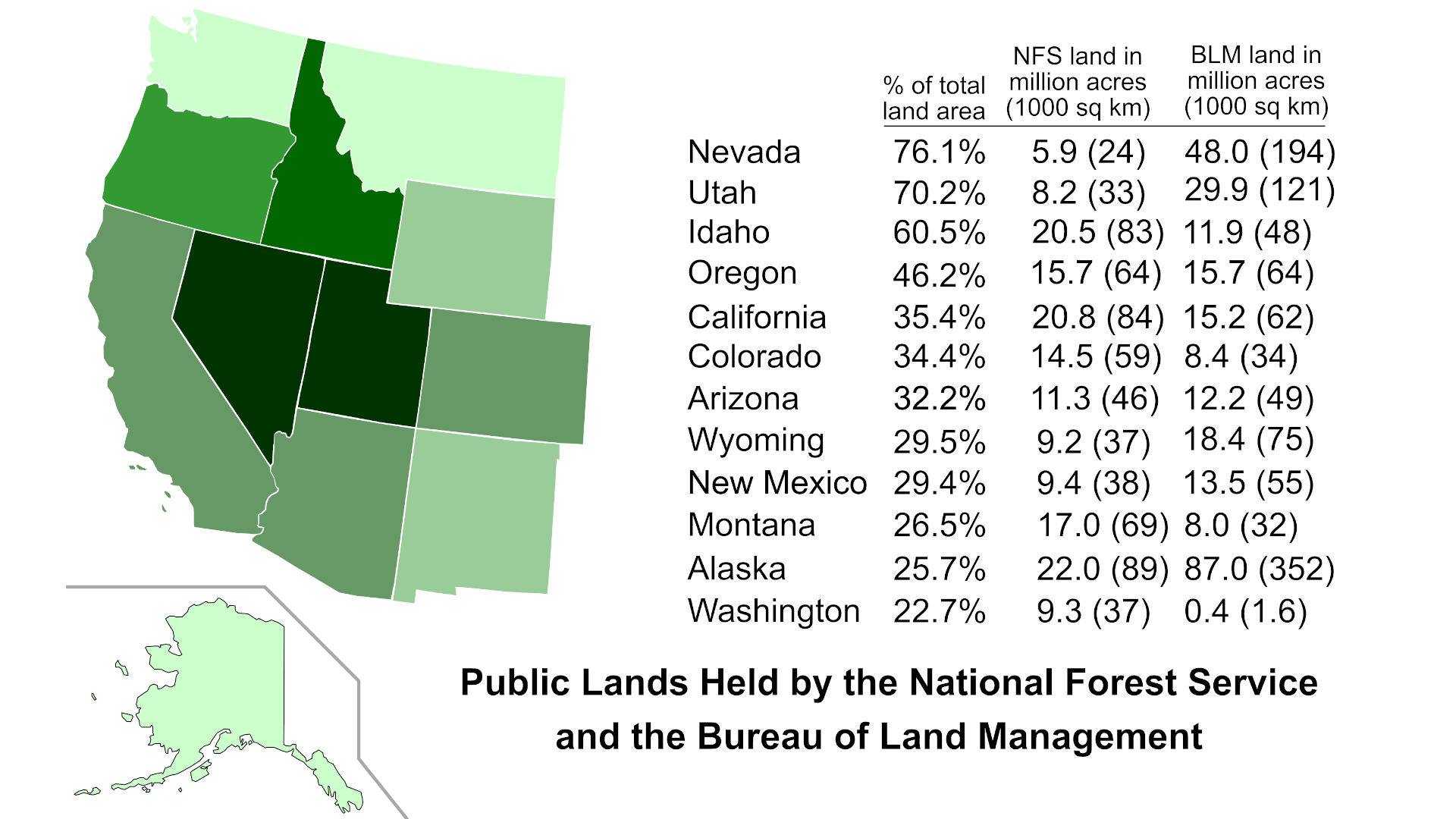

Revising the laws and regulations that govern the administration of grazing on U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land would obviously be the best way to eliminate these situations. But in the meantime, there are still ways you can take immediate action under the existing laws. Some of these suggestions are specific to Arizona, but the methodology is applicable to livestock grazing on public land all across the Western U.S.

ID Federal Agency

The first thing you need to do is to identify the local federal land agency office that’s in charge of managing the area where you witnessed the problem. Arizona has six National Forests:

- Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest (Northeastern Arizona)

- Coconino National Forest (Northern Arizona)

- Coronado National Forest (Southern Arizona)

- Kaibab National Forest (Northwestern Arizona)

- Prescott National Forest (Central Arizona)

- Tonto National Forest (Central Arizona)

Forest Service grazing management, however, is typically administered at the local Ranger District level. Each forest’s website includes contact information for its districts.

The Arizona BLM is divided into four Districts:

- Arizona Strip District (Arizona Strip)

- Colorado River District (Western Arizona)

- Gila District (Eastern & Southern Arizona)

- Phoenix District (Central Arizona)

The BLM’s grazing management is also administered locally, by the Field Offices in each district. The contact information for each office can be found on the district web pages.

ID Grazing Allotment

Another primary piece of information you’ll need is the name of the federal grazing allotment that encompasses the place where you saw the problem. The Conservation Biology Institute has online datasets that include maps of local Forest Service and BLM grazing allotments which can help you to identify it.

Also, agency websites or livestock management documents sometimes provide maps of the grazing allotments they administer, and that includes the maps listed below:

- BLM Agua Fria National Monument Grazing Allotments Map

- BLM Arizona Strip District Grazing Allotments Map

- BLM Ironwood Forest National Monument Grazing Allotments Map

- BLM Kingman Field Office Grazing Allotments Map

- BLM Las Cienegas National Conservation Area Grazing Allotments Map

- BLM Lower Sonoran Field Office Grazing Allotments Map

- BLM San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area Grazing Allotments Map

- Kaibab National Forest Grazing Allotments Maps

- Prescott National Forest Grazing Allotments Map

Of course, you can just ask the appropriate local federal land management agency office. And sometimes it’s common local knowledge, or can be discovered through Google searches or ranch real estate websites.

Determine NEPA Status

Your best opportunity to raise an issue is when the agency is in the process of completing a National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) environmental assessment (EA) of a proposed livestock management plan for the allotment you’re interested in. This process will give you an opportunity to submit written comments to the agency in response to their draft EA. If you submit comments in a timely manner, the agency is required to respond to them.

You can find a list of the active NEPA projects on each National Forest by reviewing their online quarterly Schedule of Proposed Actions (SOPA). The links to the Arizona National Forest SOPAs are listed below:

- Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests SOPA

- Coconino National Forest SOPA

- Coronado National Forest SOPA

- Kaibab National Forest SOPA

- Prescott National Forest SOPA

- Tonto National Forest SOPA

The BLM has a National NEPA Register website where you can generate a list of all of the currently active NEPA livestock grazing projects.

By submitting timely comments, you will also acquire the opportunity to officially respond if you find the final EA, and its accompanying proposed decision, to be inadequate. If the proposed decision is issued by the Forest Service, you will be able to file an objection, as per 36 CFR § 218.8. If the BLM issued the proposed decision you, can file a protest as per 43 CFR § 4160.2.

If you believe the agency’s response to your objection or protest is still inadequate, you should seek legal advice if you want to continue to pursue the issue. But you must first exhaust all of your available administrative review opportunities.

Public Record Requests

Most of the time, however, the allotment you’re interested won’t be undergoing a NEPA analysis, so you will need to submit a written complaint about the problem you found to the appropriate local agency office. But before you write it, you should conduct some research about the allotment by acquiring copies of the pertinent public records. Unfortunately, the agencies don’t maintain comprehensive online archives of these documents, so you will need to request them. The records you should ask for include:

Allotment Management Plan (AMP) – The most important record to ask for is a copy of the AMP, as it describes the livestock management plan that the allotment’s grazing permittee is required to follow. There are still a few Forest Service grazing allotments in Arizona that don’t have one, and many BLM allotments that don’t. If there’s no AMP, you should request a copy of the grazing permit. It will include some basic information, such as the maximum permitted number of livestock, and the months that grazing is allowed. There are assorted Arizona AMPs available from this site’s Document Library.

Land Health Evaluation (LHE) – If you’re concerned about a BLM allotment, request a copy of its LHE. These mandatory evaluations are completed to assess whether or not the allotment is meeting the Arizona BLM’s Standards for Rangeland Health and Guidelines for Grazing Administration. The agency is required to implement a new livestock management plan if they aren’t being met. Many Arizona BLM allotments, however, still haven’t been subjected to an LHE. Some LHEs for Arizona BLM allotments are available from this site’s Document Library.

EA – The allotment’s environmental assessment (EA), among other things, provides information about the important natural resources found on the allotment, and describes their current conditions – if any monitoring was done. An EA is always completed for an AMP and LHE. Several EAs for Arizona allotments are available from this site’s Document Library.

Annual Operating Instructions (AOI) – If it’s a Forest Service allotment, request the last several years of AOI. These documents, which are issued at the beginning of each year, describe the specific livestock management measures the permittee is required to follow for that grazing year, including the actual number of livestock authorized to graze the allotment, which is often different than the permitted number. AOIs are supposed to comply with an allotment’s AMP – if there is one. Hundreds of AOIs for Arizona Forest Service allotments are available from this site’s Document Library.

Actual Grazing Use Report – If it’s a BLM allotment, the permittee is required to submit an annual report (BLM Form 4230-5) to the local BLM field office at the beginning of each year to report the actual number of livestock that grazed the allotment the previous year. It will often be different than the permitted number.

Coordinated Resource Management Plan (CRMP) – A CRMP is typically completed, instead of an AMP, when a ranch with a public land grazing permit also includes an Arizona State Land Department grazing lease. A CRMP is supposed to coordinate the management of all of the various lands used by the ranch. They are usually drafted with the assistance of the local office of the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), and are used to help the rancher qualify for government assistance from that agency’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). An EA is rarely completed for a CRMP, even when federal land and money is involved, so you may have to ask the local NRCS office for a copy. Some CRMPs for Arizona ranches are available from this site’s Document Library.

You can contact the local federal land agency to request these records, but it’s usually more efficient to submit Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests using their FOIA websites. Requests for Forest Service records can be submitted on the USDA FOIA Public Access Website. Requests for BLM records can be submitted on the federal FOIA.gov website.

You also might be able to find some of these records online through Google searches, especially if they were recently issued. And the Arizona State Library’s Arizona Memory Project website might have copies of older records.

Another online source of relevant public records are the biological opinions from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. They are issued when federal land management projects, such as a proposed grazing plans, may affect threatened or endangered species. They can include conservation measures the grazing permittee is required to follow in order to comply with the Endangered Species Act.

Follow The Money

In addition to acquiring the allotment’s grazing management records, you might want to find out how much government financial assistance the permittee has received. It’s not uncommon for public land ranchers to resist livestock management measures that protect the environment, such as excluding cattle from riparian areas, while simultaneously collecting substantial government subsidies. Highlighting this hypocritical behavior can add weight to your complaint. But first you will need the name of the allotment’s grazing permittee, and that might take some work, especially since the agencies are reluctant to divulge the identities of grazing permittees for political reasons – even though it’s public information.

However, if it’s a BLM allotment, you can use their public Rangeland Administration System Reports website to identify the permittee. First, generate the Allotment Information report for the local Field Office where the allotment is located. Then, find your allotment on the list, and copy its Authorization Number. Next, go back to the home page and generate the office’s Operator Information report and find the matching Authorization Number on the list of permittees (operators). Another feature of this website is that you can download the Excel and PDF versions of the reports you generate to your desktop. (So, even if the website, or some of its information, is removed from the Internet, you will still have the information as of the date it was downloaded.)

It’s more difficult to identify the permittee for a Forest Service grazing allotment in Arizona. The agency’s Southwestern Regional Office has been redacting permittee names from the grazing management documents they release to the public for the last several years. This practice is of very questionable legality, and a FOIA appeal was filed in April 2021. (On July 7, 2023, the Forest Service finally issued their FOIA appeal response wherein they directed that all of the requested documents should be provided without any redactions. The agency’s Southwestern Regional Office, however, interpreted this to only apply to the specific FOIA request named in the appeal, and has continued to redact permittee names from grazing documents released in response to subsequent FOIA requests. Another FOIA appeal, #2023-FS-WO-00104-A, was submitted on August 20, 2023, to challenge this continued practice.)

But in the meantime, there are other ways you might be able to identify the permittee. For instance, if you know the name of the ranch that’s associated with the allotment, you can search the Arizona Corporation Commission website for that ranch company’s name, as there might by a limited liability corporation (LLC) that uses that name, and LLC’s online records will list the names of the owners. You can also search private property records on county recorder websites, as public land ranches include private “base property” parcels that are typically located adjacent to the allotment. Furthermore, some of the government assistance programs that ranchers take advantage of include permittee names in their project records. The biological opinions issued by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife service often identify the affected permittees too.

If the allotment is part of a ranch that includes an adjacent Arizona state grazing lease, you can use the State Land Department’s online Parcel Viewer website to find the name of the lease holder, and that will usually be the permittee. This can be verified by reviewing a copy of the state grazing lease application, because lease applicants must reveal if there’s a federal grazing allotment associated with the ranch that holds the state lease.

Of course, you can always just try Google searches to attempt to identify the permittee. And if you have a Newspapers.com account, you can search historical newspaper archives for clues.

Once you identify the grazing allotment and it’s permittee, you can search online on this site for the government assistance the ranch might have received.

Submit A Complaint

You can call your local applicable federal agency office and describe your complaint over the phone. But written complaints, sent by mail or email, create permanent documentation that can be very useful, especially if you are eventually forced to seek a resolution through legal action. Also, when you submit written comments on a specific BLM allotment, you automatically become an “interested public” as per 43 CFR § 4100.0-5. The BLM is then required to contact you regarding any livestock management changes on the allotment, as per 43 CFR § 4120.2. (The BLM, however, has a very poor record of complying with this legal requirement.)

If you submit your written complaint by email, which is the preferred method these days, don’t forget to attach PDF copies of the documents you’ve referenced, and include any photos you took of the situation. Also don’t forget to provide your contact information, including mailing address and phone number.

Furthermore, share copies of your complaint with local conservation groups. In fact, you might want to “Cc:” them on your complaint so the agency knows you are involving them. Also share your complaint on social media, and don’t forget to include your photos in the post. And remember to send copies of the complaint to your U.S. Senators and Representatives. They regularly hear from agricultural lobbyists, so that needs to be counterbalanced.

If all of this seems unnecessarily complicated, you’re right. Public land ranchers and their political and bureaucratic supporters don’t want you to know what’s going on, or have much say in livestock management on public land. That’s another reason to get involved.

2 thoughts on “Be A Public Land Grazing Activist”

Wild horses & burros live on federal public lands. They, the public are legally-entitled to have a seat at the table when decisions are made about these lands and the impact on horses’ access to food and water. That seat has been pulled out from under us. What gave us a seat at the table? Herd Management Area Plans. HMAPs are prepared site-by-site for the wild herds with public participation. HMAPs are not being done. Public is being muzzled. Relentless roundups & removals of horses will continue until HMAPs are done. Why don’t we mandate HMAPs? HMAPs are mandated already. Isn’t it neglect by Bureau of Land Management to NOT have prepared these plans? Yes. What can the public do about it? Demand HMAPs. They are a win-win for wild horses & burros, public lands, the mass public. HMAPs protect us all, like a protective door, and without them the door is wide open to bad practices & corruption and we are all screwed. Fertility control is no substitute for HMAPs. (There are 177 areas where wild horses live that should have HMAPs. How many exist? Less than 10.)

Well, never heard this before! Certainly seems to be something that ALL Wild Horse advocates should be aware of, right? Nice to see a complete description of how “lay” people can go about sort of putting a monkeywrench in the works, so to speak! But HMAPs? I will pass this along to others.