The Arizona Game & Fish Department is involved in the business of cattle ranching on public land, despite the fact its only legal purpose is to administer the “laws of the state relating to wildlife.” The Department’s management of the Horseshoe Ranch property, which it acquired in 2011, is a good example of how they’ve strayed from this legal requirement. The ranch’s purchase was the result of decisions made by the Department’s governing body, the politically appointed Arizona Game & Fish Commission. The Department’s 2011 Annual Report, along with its public announcements about the ranch’s purchase, stated that one of the reasons the Commission agreed to buy it was to preserve “the tradition of ranching in central Arizona.”

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land that surrounds the ranch’s base property in Yavapai County wasn’t always public land. Land trades were made between the BLM and the Arizona State Land Department in 1988 and 1991 that brought 62,700 acres of local land into BLM ownership. The lands acquired by the BLM included important natural resources, like desert riparian areas, which gained some protection under federal ownership.

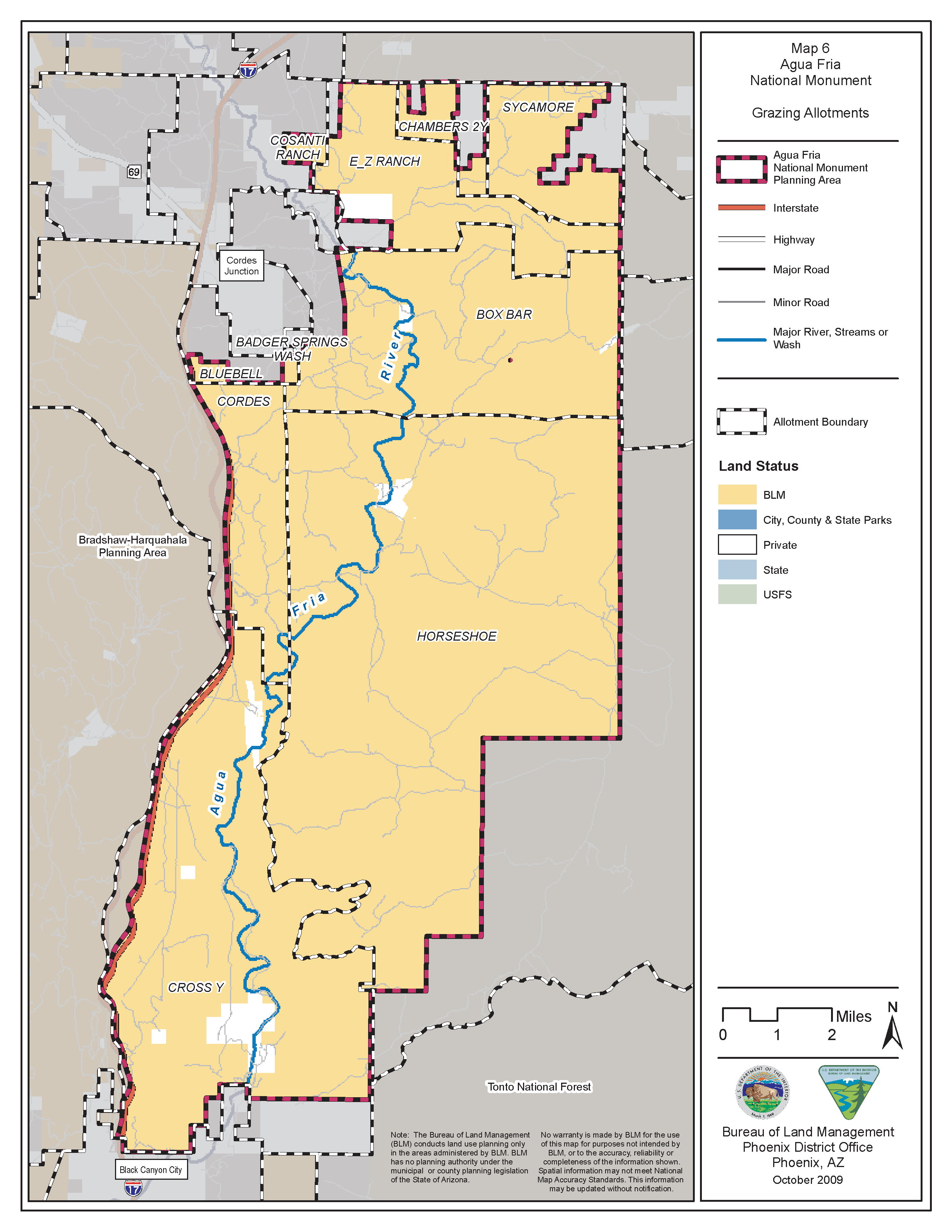

The BLM created new federal grazing allotments from these acquired acres. The former state land that had been leased for grazing to the Horseshoe Ranch became the BLM’s new 32,388-acre Horseshoe allotment, and was permitted to the Horseshoe Ranch. It was adjacent to the existing 35,899-acre Copper Creek grazing allotment administered by the Tonto National Forest, which was already permitted to the Horseshoe Ranch.

But the land exchanges worried many Arizona ranchers, especially the ones directly affected by the trades, because they suspected the BLM would require them to make changes to improve their livestock management. (The State Land Department is notorious for not monitoring livestock management on the land it leases for grazing.)

The first major change for the Horseshoe Ranch, however, didn’t happen until the completion of the Horseshoe Ranch Coordinated Resource Management Plan (CRMP) in 1998. And even then, it was the grazing permittee, Richard S. “Dick” Wilcox, owner of CTW Cattle Company, that initiated the project.

The 1998 CRMP called for the implementation of a plan to coordinate grazing management on the two adjacent federal grazing allotments and authorized a total herd of about 500 cows yearlong, which was less than the maximum permitted numbers, along with up to 950 yearlings for 6 months. It included pasture rotations, and grazing was restricted in the riparian areas on both allotments to the winter season, from November through February. It also called for large investments in new fences and livestock waters and, of course, government financial assistance paid for much of it. The Game & Fish Department, for example, contributed a Habitat Partnership Committee (HPC) grant of $9,000 for a new pump to supply water to a new cattle trough.

Ranchers in the Horseshoe Ranch area began to worry again when President Bill Clinton used the Antiquities Act of 1906 to proclaim the creation of the 72,000 acre Agua Fria National Monument from local BLM land on January 11, 2000. It included the BLM’s Horseshoe grazing allotment, along with several others.

Clinton’s proclamation stated that existing livestock grazing would “continue” to be permitted within the monument, but it had to be managed to “implement the purposes of this proclamation.” That did little to comfort the local ranchers, so on January 13 the BLM responded by releasing an interim monument management policy that stated they intended to maintain the existing situation, “except where changes are necessary to comply with the proclamation.”

Charles W. Wilcox, Dick’s son, had taken over the Horseshoe Ranch by the time the Agua Fria National Monument was created in 2000. He was reportedly running it as a dude ranch with cattle. The cattle ranching operation was likely only marginally profitable because the two grazing allotments are mostly Sonoran desert scrub and semi-desert grassland. The year 2000 was also at the beginning of Arizona’s ongoing long-term drought, and in 2002 the drought got so bad that the Tonto ordered its grazing permittees to remove their cattle from the Forest. Wilcox put the ranch up for sale that year.

In January 2004 he sold it to Red Mountain Mining, Inc., owned by mining entrepreneur Dale L. Longbrake, who quickly transferred ownership to his Red Mountain Properties, LLC. Longbrake didn’t buy the Horseshoe Ranch because he wanted to be in the cattle business. He wanted to make a land trade with the BLM wherein he would trade the 199-acre Horseshoe Ranch base property for 200 acres of BLM land in northeast Mesa, Arizona, where he wanted to mine decorative landscaping rock.

But the trade didn’t happen, largely because of resistance against the proposed mining operation from local residents in Mesa, so Longbrake eventually put the ranch up for sale in 2007. Cattle grazing on the Copper Creek allotment had ended in 2005 after it was burned in the Cave Creek Complex Wildfire. And grazing had ceased on the Horseshoe allotment in 2006, according to the allotment’s 2018 Land Health Evaluation (LHE).

Some BLM officials reportedly had wanted to acquire the Horseshoe Ranch base property inholding ever since the BLM land that surrounded it was included in the Agua Fria National Monument. However, without a land trade, the BLM had to find the money to buy it. But local BLM officials pointed out that the State Historic Preservation Office wanted the ranch’s headquarters buildings preserved, and claimed their agency wouldn’t be able to afford to maintain them. This was despite the fact that after the BLM acquired the historic Empire Ranch base property in southern Arizona in 1988, they were able to open up the ranch’s buildings to the public 365 days a year, make them available for local public events.

The Horseshoe Ranch didn’t sell and the ranch’s mortgage went into foreclosure, so the BLM and the Game & Fish Department asked for help from the Trust for Public Land. The Department told the trust it wanted it to use use the ranch headquarters for public education and research. The trust agreed to temporarily refinance Longbrake’s loan in order to halt a scheduled foreclosure auction and give the Department the time it needed to get money to buy the ranch.

Game & Fish Purchases The Horseshoe Ranch

After some complicated financial transactions, the Arizona Game & Fish Commission approved the Department’s proposal to purchase the Horseshoe Ranch at their October 2010 meeting. Gaining control of the ranch’s two federal grazing allotments, because of the important wildlife habitat found on them, was stated as a primary objective of acquiring the ranch, so the Commission also approved a plan to subsequently enter into an interagency agreement with the BLM and Tonto National Forest for the management of the allotments.

The $3.3 million needed to buy the Horseshoe Ranch came from several sources. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) contributed a $1 million Endangered Species Recovery Land Acquisition Grant to help purchase the base property, and the Department provided another $1.59 million from its Heritage Fund for that purpose. The Department also contributed two HPC grants totaling $710,000 that were used to acquire the associated grazing permits for the Horseshoe and Copper Creek allotments. The Arizona Antelope Foundation (AAF), a hunter group that had “adopted” the ranch in 2006, contributed most of the money that was in these HPC grants. Game & Fish also spent more than $35,000 in acquisition costs to complete the ranch transaction. The Department’s purchase of the ranch was finalized in March 2011.

| SOURCE | PROGRAM | AMOUNT | PURPOSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Game & Fish | HPC Grant #08-607 | $135,000 | Acquire Federal Grazing Permits |

| USFWS | RLA Grant | $1,000,000 | Purchase Ranch Base Property |

| Game & Fish | Heritage Fund | $1,590,000 | Purchase Ranch Base Property |

| Game & Fish | HPC Grant #10-607 | $575,000 | Acquire Federal Grazing Permits |

| Game & Fish | $35,424 | Acquisition Costs | |

| TOTAL $3,335,424 |

By August 2011 the Department had signed the interagency agreement with the BLM and Forest Service for the management of the ranch’s two grazing allotments. It included some unique, and unprecedented, provisions regarding the administration of the associated grazing permits.

It also included some political declarations. The Preamble, for example, stated:

“The Parties to this agreement feel a unique opportunity exists to developing alternatives, including research, to managing the Allotments that preserve the domestic livestock grazing tradition”

And the agreement’s Statement of Mutual Benefit and Interests stated:

“The conservation of the tradition of ranching and livestock grazing as a suitable and historically admired utilization of these lands”

Then in October it was announced that a new CRMP would be implemented on the Horseshoe Ranch. It would be drafted using a collaborative public planning process similar to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) public planning process. But this process was suspiciously different, because it included a mandatory goal to “maintain or improve” the ranching operation, and by federal law, NEPA environmental assessments of livestock management plans for public lands must always consider the benefits of a “no grazing” alternative.

In January 2012 the Department signed a 3-year lease with the recently formed JH Cattle Co. LLC, owned by John T. Holbrook, for use of the Horseshoe Ranch base property to operate a cattle ranching operation on the two federal grazing allotments. The Department had interviewed more than a dozen applicants, and when asked about being selected, Holbrook said he felt “very lucky.”

Indeed, the lease set the rent for the use of the ranch base property, which had cost the Department $2.59 million, at just $200 per month. It also set the monthly grazing fee for the use of the two grazing allotments at just $5.50 per head of livestock. Holbrook, however, also had to pay the federal grazing fee for use of the allotments since the Department was forced to waive the permits to his company because state agencies are prohibited by federal law from holding grazing permits. But the federal grazing fee was just $1.35 per month in 2012, which meant his company’s total monthly grazing fee was only $6.85 per head.

Cattle were released onto the two grazing allotments in 2012, even though the area was experiencing a severe drought, neither allotment had been grazed for years, and the ranch’s new CRMP hadn’t been completed. Furthermore, the BLM had not completed an LHE for the Horseshoe allotment to assess its compliance with the Arizona Standards for Rangeland Health and Guidelines for Grazing Administration, as required by the Rangeland Reform ’94 public land grazing regulatory reforms.

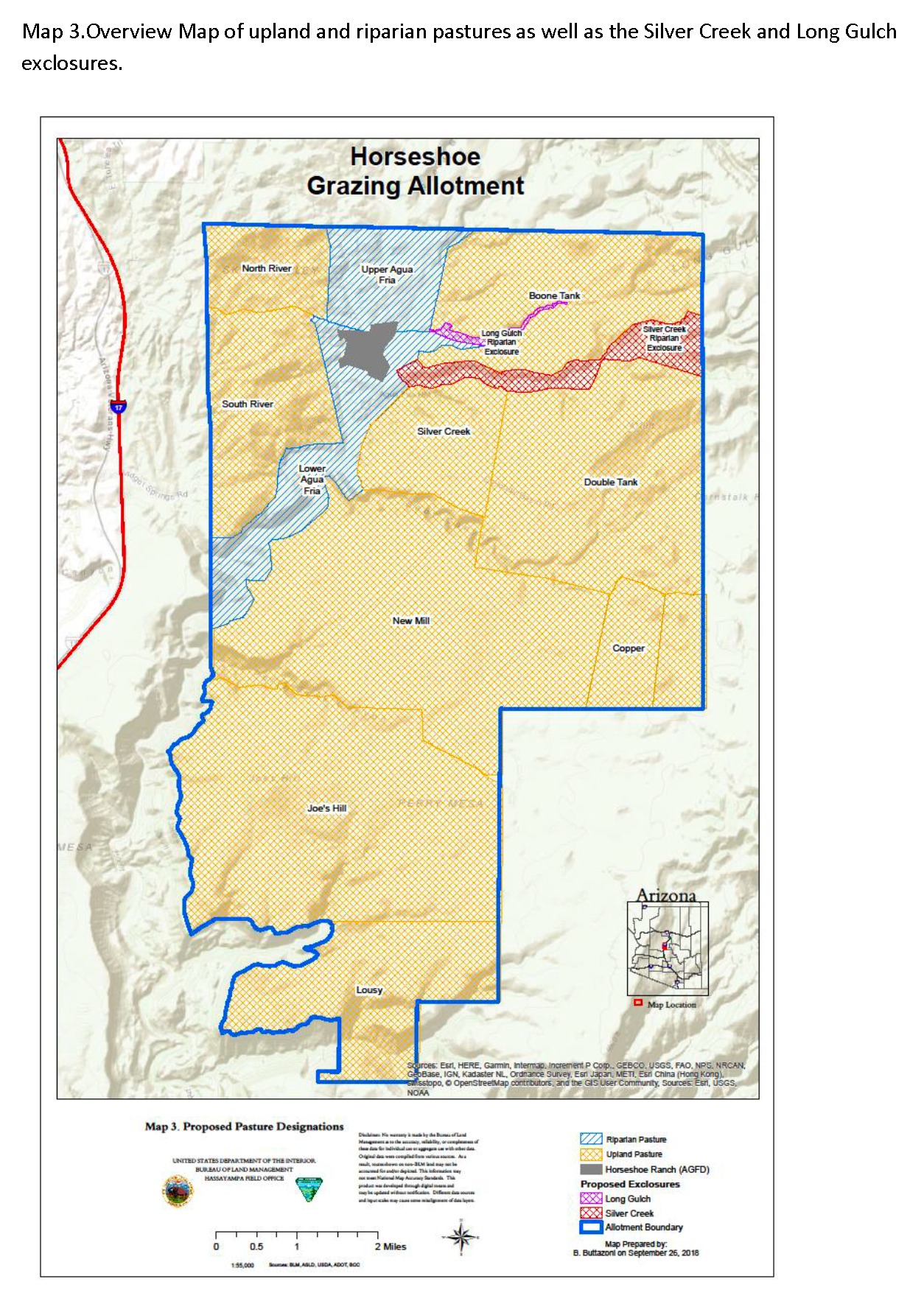

In 2014 a draft Horseshoe Ranch CRMP was released that included some proposed improvements over the 1998 CRMP and the subsequent 2010 Agua Fria National Monument Resource Management Plan (RMP). The most significant ones were the creation of riparian exclosures on the BLM’s Horseshoe grazing allotment to exclude cattle from Long Gulch and Silver Creek, and the suspension of surface water diversions from Silver Creek, Indian Creek, and the Agua Fria River when it ran.

But the draft CRMP also proposed the construction of 35 expensive range “improvements” in order to help maximize the number of actual cattle that could graze the allotments.

In 2015 the Department renewed the lease for the Horseshoe Ranch with the JH Cattle Co. LLC for a period of 10 years. Holbrook said he asked for a longer lease because he had discovered that every fence and livestock water were “busted” and he needed a longer lease to justify his investments in the repairs. Under the new lease the monthly rent for the use of the base property was still just $200, and the lease’s monthly grazing fee was still $5.50 per head of livestock.

A final decision was never issued for the new CRMP, because the BLM and Forest Service are required by law to follow different procedures for implementing livestock management plans on their grazing allotments. Furthermore, the “collaborative” CRMP planning process hadn’t met the required NEPA legal requirements. The Tonto eventually issued a final environmental assessment (EA) for the Copper Creek allotment in 2017, and the final decision in 2018. The BLM finally issued an LHE for the Horseshoe allotment in 2018, a final EA in September 2020, and the final decision that November. The decision for the Copper Creek allotment set the maximum permitted number of livestock at 500 cattle yearlong, with up to 250 yearlings for 4.5 months. The Horseshoe allotment decision allowed up to 381 cattle yearlong.

These decisions mostly complied with the draft CRMP, as was called for in the interagency agreement. But there were a couple of significant differences in the BLM’s decision for the Horseshoe allotment – for the worse. First, the construction of the fence to create a riparian exclosure to exclude cattle from Long Gulch wasn’t included. Furthermore, the suspension of surface water diversions from Silver Creek was also missing, along with the removal of the steel pipeline that was used to pump water uphill from the creek.

These changes contradicted the biological assessment (BA) the BLM had submitted to the USFWS in October 2018 in order get concurrence that the proposed grazing plan for the Horseshoe allotment would comply with the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The BA, like the prior draft CRMP, included the riparian exclosure to protect Long Gulch, along with the suspension of surface water diversions from Silver Creek. The ESA concurrence letter the USFWS sent the BLM in November 2018 was based upon the grazing plan described in the BA.

When asked about these changes, Holbrook explained that Long Gulch has been included within the new riparian pasture that will allow grazing to be restricted in the Agua Fria River to the winter season only. He also said he still has no intention of diverting water from Silver Creek in order to water cattle on the nearby uplands, and he intends to remove the steel pipeline that was used for that purpose. But he pointed out that the Game & Fish Department still holds a right to divert water from Silver Creek for domestic use at the ranch base property.

Game & Fish officials have often claimed that the primary reason they wanted to buy the Horseshoe Ranch was to obtain control of the Horseshoe Ranch’s two grazing allotments because they have important wildlife habitat. But it’s difficult to believe that facilitating the release of hundreds of cattle upon an inherently arid ecosystem that’s suffered from a long-term drought and wildfire improved the local habitat. New livestock waters approved for the uplands will be available for wildlife use, but there were already several natural riparian areas and springs where wildlife could find water.

Management Of Horseshoe Ranch Base Property

The $2.59 million the Game & Fish Department specifically used to purchase the Horseshoe Ranch base property came from government grants that had legal restrictions regarding their use. The $1 million USFWS Section 6 non-traditional Recovery Land Acquisition (RLA) grant was required to be used for threatened and endangered species conservation. The $1.59 million Heritage Fund grant had to be spent for sensitive sensitive wildlife habitat Identification, Inventory, Protection, Acquisition, and Management (IIPAM). The grantors understood that the acquisition of the ranch would allow the Department to control the two federal grazing allotments where federally listed and sensitive wildlife species were found. But the management of the ranch’s base property also needed to contribute to the recovery of these species.

The Department submitted its Horseshoe Ranch Wildlife Habitat Enhancement Plan for the ranch’s base property to the USFWS for their approval in 2017. It had three major components:

- establish populations of endangered Gila chub, Gila topminnow, desert pupfish, and threatened Northern Mexican garter snake populations in the property’s existing 2.4 acre-feet capacity pond to be potential sources for their reintroduction into the Agua Fria watershed;

- establish a 3-acre experimental cottonwood garden on the property along the Agua Fria River for use in climate change and genetics research, which also might be used by the threatened yellow-billed cuckoo; and

- plant annual upland game bird seed crops, and native grasses and forbs, on about 15 acres of fallow cropland on the property near the ranch headquarters that would benefit upland game birds and pollinator species, and also be periodically grazed by the lessee’s horses or cattle.

All of these relied upon pumping underground water from wells located on the ranch property. But that could lower the local water table and negatively impact the several acres of riparian habitat on the property along the Agua Fria River, especially during drought. Game & Fish recognized this and implemented several conservation measures, such as lining the pond, and upgrading the irrigation equipment, to reduce the ranch’s water use. They also began using monitoring wells to track changes in the water table.

But before the flat land in the floodplain of the Agua Fria River on the ranch property was converted to cropland, it was likely a mesquite bosque (forest), which is a very important type of wildlife habitat in the Desert Southwest. It would only take a few years for it to revert to that if the farming operation were abandoned, and that would also significantly reduce the need to pump groundwater.

A primary reason the Department pumps water to irrigate the fields, according to its Land & Water Program Supervisor, Jim Ruff, is to exercise the agency’s water rights, so they don’t lose them. When Game & Fish bought the Horseshoe Ranch it also acquired all of its associated water rights. In addition to the rights to the wells on the ranch property, they included the rights to surface water diversions to the ranch property from Silver Creek and Long Gulch.

Arizona is a “use it or lose it” Western water law state, so water rights can be forfeited if the water isn’t regularly put to a “beneficial” use. The enactment of Arizona HB 2056 in 2021 changed that requirement so a water right could be retained even though it wasn’t being used if a holder submits a potentially renewable temporary water conservation plan, up to 10 years long, that’s approved by the Director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources. But this new procedure hasn’t been fully implemented yet, and the department’s director is a political appointee.

In the meantime, it’s difficult to understand how curtailing the farming operation on the ranch property could cause a big problem. Even if the water rights to the wells were reduced for lack of use, it seems impossible that another party could get access to them, since the Department owns the property where they are located.

The legal situation with the Department’s surface water rights for the diversions of water from Silver Creek and Long Gulch to the ranch property is different because Arizona’s water laws provide for establishing an instream flow right to cease and prevent surface water diversions from a stream for the beneficial purposes of recreation or wildlife habitat. An applicant for an instream flow right, however, must provide “at least five years of continuous streamflow measurement data.” But the Department hasn’t collected that data, according to Mr. Ruff.

The 2014 draft CRMP called for the suspension of surface water diversions to the ranch’s base property, and the Department’s improvements to the property’s well systems were designed to help facilitate that. But according to Mr. Ruff, the Department’s surface water rights for Silver Creek and Long Gulch “are being used consistent with water rights associated with the acquisition.”

Gift Clause Of Arizona Constitution

The Department’s lease of the ranch’s multimillion-dollar base property for just $200 per month and the use of the two associated federal grazing allotments for just $5.50 per animal per month might be a violation of the gift clause in Article 9, Section 7 the Arizona Constitution. It prohibits any state agency to, “ever give or loan its credit in the aid of, or make any donation or grant, by subsidy or otherwise, to any individual, association, or corporation.” The Department addressed this law in its substantive policy statement regarding its land use agreements:

When the Commission determines a land use agreement will provide benefits to the Department or benefit wildlife, the Commission may consider those benefits in adjusting the fair rental value and may approve and execute a land use agreement, which will reflect such benefit or enhancement.

But a state agency’s substantive policy statement doesn’t have the force of law and can’t supersede the state constitution.

In regards to the ranch’s associated grazing permits, according to ranch brokers the current (2021) market value of federal grazing permits in Arizona is about $2,000 to $5,000 per animal unit. The Horseshoe allotment is currently permitted for up to 381 head yearlong, and the Copper Creek for up to 500 head, for a total of 881. So, assuming the lower value of $2,000 per animal unit because of the continuing drought, that still comes out to a current market value of about $1.76 million for the two grazing permits.

As mentioned previously, the Department had to waive the permits to the lessee because federal law prohibits state agencies from holding grazing permits. The lessee apparently didn’t have to pay for them because the 2011 interagency agreement to manage the two grazing allotments allows the Department to retain control of the permits if the Horseshoe Ranch gets a new lessee. (In the agreement, the BLM recognized the owner of the ranch base property, and it’s lessees, as the preferred holders of the Horseshoe allotment’s permit. And the Tonto National Forest agreed to only issue annual temporary grazing permits for the Copper Creek allotment to the ranch’s lessees to avoid issuing regular 10-year grazing permits.) But even though these unique provisions in the agreement allow Game & Fish to retain control of the permits, the JH Cattle Co. LLC gets to use them for just $5.50 per animal per month. Furthermore, the Holbrooks are also operating a performance horse breeding operation at the ranch’s base property, which they are now calling the Rugged Ranch.

The Horseshoe Ranch Could Have Been Managed Differently

The Game & Fish Department has obviously had to make compromises because of the Commission’s decision to manage the Horseshoe Ranch as an active cattle ranch. So, how could things have been different if the Commission had prioritized the protection and improvement of the local wildlife habitat instead?

The ranch’s previous owner wanted to get paid for the permits for the two federal grazing allotments, so the Department had to buy them or they probably would have been sold to ranchers that held grazing permits for adjacent allotments. But the Department could have proceeded differently after they obtained the permits. The allotments hadn’t been grazed for several years, so the Department could have asked the BLM and Forest Service to extend their existing nonuse status for conservation purposes until a new CRMP was completed using the required NEPA public planning process.

Game & Fish would still have been required to find a lessee in order to retain control of the permits, but since that lessee would have gotten the use of the allotments without having to pay for the permits, there still would have been plenty of applicants, no matter how long it might have taken for grazing to actually resume, and whatever the terms of the new CRMP.

Moreover, during the NEPA planning process the Department could have asked that the borders of the BLM’s Horseshoe allotment be redrawn to remove the existing pastures that included the important riparian areas of the Agua Fria River, Silver Creek, and Indian Creek. That would have saved a lot of public money building fences to create riparian pastures. Moreover, it would have eliminated winter-only grazing in these riparian areas, which isn’t as damaging as growing season grazing, but is only a half-measure because it doesn’t do riparian areas any good. For example, the photos below show what the allotment’s Silver Creek looked like after the November 1, 2020, to March 1, 2021, “winter season” riparian grazing period.

Also, removing all nearby livestock grazing from the riparian areas could have made it easier for the Department to convert their existing surface rights to instream flow rights.

The ranch’s base property could have been managed differently too. The use of the Horseshoe Ranch property as a base of operations for the lessee using the federal grazing allotments has resulted in it being closed to the public, except for an occasional Commission meeting or infrequent use as a volunteer rallying spot. And the Department has had to spend lots of money to repair the long-neglected headquarters buildings so they could be used by the grazing lessee.

But the Department could have told potential grazing lessees that they wouldn’t be allowed to use the ranch property as their operational headquarters, couldn’t keep their horses there, and would have to use corrals out on the allotments for cattle roundups.

This strategy would have allowed the ranch property to be opened to the public for a variety of uses, such as a trailhead and nature center. Visitors could have been charged a small fee to help with the property’s upkeep. It’s likely the Department would have collected more than $200 per month.

The Department’s willingness to invest heavily in maintaining the property’s infrastructure to support a ranching operation and the efforts to maintain the full commercial water rights raises the question of whether or not the Commission is considering disposing of the Horseshoe Ranch someday by selling it to a rancher. If they are, it might be due to Arizona SB 1212, which was passed in 1995 to revise the Game & Fish Department’s Heritage Fund. It included a property disposal clause, promoted by Rep. Rusty Bowers, R-Mesa, which allows the Department to dispose of any land it has acquired to protect federally listed species if the species “no longer qualifies” as a listed species. But a USFWS Section 6 Non-traditional Recovery Land Acquisition (RLA) grant was used to help purchase the Horseshoe Ranch property, and recipients of these grants are required to set the land aside in perpetuity for species conservation. Changing that legal requirement, however, might be a political objective of some people.

Taxpayers Are Paying For The Horseshoe Ranch

Like most public land ranches in the West’s arid regions, taxpayers are paying to support the livestock operation on the Horsehoe Ranch. The table below shows the government assistance that has benefited the ranch. Much of it wouldn’t have been unnecessary if the Commission hadn’t decided to resume grazing on the ranch.

Government Assistance For Ranchers Program Key

The EQIP program absorbed the NRCS Wildlife Habitat Incentives Program (WHIP) after 2014.

The Arizona EWP Drought Program was discontinued in 2001 after a critical audit.

Note: Open Space Reserve Grants became LCCGP Grants after 2002.

This fund was created by a one-time $3.5 million appropriation by the Legislature in 2006.

Note: These grants were previously called Section 319 nonpoint source (NPS) water pollution prevention grants.

| YEARS | PROGRAM | AMOUNT | PROJECT NAME |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | HPC #13-601 | $1,058 | Brooklyn Well Solar Water Pump |

| 2014 | HPC #13-602 | $30,000 | Copper Creek Allotment Dirt Tank Cleanouts |

| 2015 | HPC #14-601* | $60,000 | Kill Coyotes to Protect Pronghorn & Mule Deer Fawns |

| 2015-2020 | LFP | $105,020 | JH Cattle Company LLC |

| 2020-2021 | LFP | $98,147 | John T. Holbrook |

| 2022-2023 | ELRP | $60,820 | John T. Holbrook |

| 2023 | LFP | $53,442 | John T. Holbrook |

| 2024 | LFP | $15,812 | John T. Holbrook |

| $424,299 | TOTAL 2014 - 2024 | ||

The Bottom Line

The bottom line regarding the Arizona Game & Fish Commission’s management of the Horseshoe Ranch is that they made a decision to pursue a policy outside of their mandate to create a showcase project to try and preserve the Western “lost cause” myth that ranching on arid public land is a beneficial tradition that’s good for the land and wildlife.

Updates

On March 12, 2024, the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity sued the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for Endangered Species Act violations for failing to ensure that cattle grazing doesn’t continue to destroy Western Yellow-billed Cuckoo and Gila Chub critical habitat on Agua Fria National Monument.

In January 2025, Arizona Rep. Gail Griffin (R-Hereford), chair of the House Natural Resources, Energy and Water Committee, introduced HB 2083, which would require that at least one member of the five-member Arizona Game & Fish Commission be rancher. Less than 0.5% of Arizona’s population are ranchers, and many of them don't rely on ranching for their primary source of income.

3 thoughts on “Arizona Game & Fish Department Is In The Ranching Business”

A major reason for purchasing the property was to improve the range conditions for the dwindling pronghorn population. For example, to maintain an eight-inch stubble height for fawning cover, which was lacking in most of the surrounding allotments. But that didn’t happen and the herd of over 300 pronghorn declined to where there’s not even a hunting opportunity anymore.

Why is the Silver Creek canyon access from Rt 9269 now Posted as private property?

All I can say is, you people will do anything you can to shut down cattle ranching in a Arizona. Grazing cattle is actually extremely beneficial to the environment. Including but not limited to, prevention of wildfires due to grazing of under brush and “invasive species”, their natural ability to fertilize the soil, as well as the fact that cattle don’t have top teeth, so they are not physically capable of pulling feed from the root out of the ground, resulting in “grubbing out” a certain area. Cattle ranching will always be alive and well in the state of Arizona, and I commend you for trying so hard to make public grazing allotments a thing of the past, however it will simply never happen. God Bless y’all.